In 1971, Australian historian Ross Terrill visited the People’s Republic of China and he subsequently chronicled the trip in the 1972 book 800,000,000: The Real China. The title of the book was a reference to the PRC’s population at that time. As of April 2020, the population of the PRC is approaching 1.4 billion people.

The excerpt below is Terrill’s account of his meeting with Premier Zhou Enlai, from chapter 12 of the above-noted book. In the author’s original work, names are presented via the Wade-Giles method of transliteration ( “Chou En-Lai”) as opposed to the more modern Pinyin method (“Zhou Enlai”). The text is presented under the terms of Fair Use.

The prelude to a meeting with a Chinese leader is always the same. There is no fixed appointment time, but word is one day given “not to leave the hotel.” Suddenly a phone call comes to say that the man you are to see has just left the compound where the Chinese leadership works. You leave immediately for the Great Hall of the People. The idea is to have the two parties arrive at the same time.

The prelude to a meeting with a Chinese leader is always the same. There is no fixed appointment time, but word is one day given “not to leave the hotel.” Suddenly a phone call comes to say that the man you are to see has just left the compound where the Chinese leadership works. You leave immediately for the Great Hall of the People. The idea is to have the two parties arrive at the same time.

With Chou En-lai, Premier for twenty-two years and (last summer) number three man in China’s government, the call is likely to come late at night. This war-horse of revolution, “seventy-three years young,” works until 4:00 a.m. or 5:00 a.m., then sleeps until midmorning. Our group (I was with my countryman E. Gough Whitlam, leader of the Australian Labor party) was advised late on July 5 to stay about the Peking Hotel. There would be an “interesting film” that evening. The Foreign Ministry official did not explain why we were advised to put on suits and ties for the occasion. Just after 9:00 p.m. a call came: the film was off, Chou En-lai was on.

The Great Hall of the People is really the Great Hall of the Government. Only on highly formal occasions do the masses view its murals and tread its crimson carpets. A stone oblong in semi-Chinese style, it was built in a mere ten months around the time of the Great Leap Forward. Its fawn solidity stands guard over the biggest square in the world, Tien An Men; the Imperial City is to the left, the big museums opposite. The building’s area of 560,000 square feet includes an auditorium for 10,000 people, a room decorated in the style of each of China’s provinces, and sparsely furnished halls such as the East Room, where we found the Premier.

He enters from one door, we from another. A red badge with the Chinese characters “Serve the People” lights up his tunic. He is all in gray except for black socks inside leather sandals and black hair showing strongly through silver fringes. Introduced to him by Ma Yu-chen of the Foreign Ministry (the man who at¬tended James Reston at his hospital bed), I suddenly realized that he is a slim, short man. We talked for a moment of the background to the Whitlam visit; then he asked where I learned Chinese. Told “in America,” he smiled broadly and said, “That is a fine thing, to learn Chinese in America!”

Recalling his amazing career over half a century, I marveled at his freshness. This man has been a member of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party since 1927 (well before Mao); was forty-five years ago a close colleague of Chiang Kai-shek’s in Canton; played leftist politics in Europe at the time of Lenin; covered the last miles of the Long March through north Shensi in 1935 on a stretcher, gravely ill. Now he reaches across an epoch of China’s modern history to face Richard Nixon in the Ping-Pong diplomacy of the 1970s.

Though he is like David to Mr. Whitlam’s Goliath (the Australian is six feet four), you quickly forget his height; it is his face and hands which rivet every eye in the room for the next two hours. The expression is tough, even forbidding, yet sometimes it melts into the disarming smile which used to flutter the hearts of foreign ladies in Chungking (Mr. Chou was the Communist rep resentative in Chiang Kai-shek’s capital during World War II). The eyes are steely, but they laugh when he wants them to. The voice, too, has double possibilities. One moment he is nearly whispering, weary and modest. The next he is soaring to contradict his visitor, and the streaky, sensual voice projects across the hall. From a side angle, a rather flat nose takes away all his fierceness. The mouth is low in the face and set forward tautly, giving a grim grandeur to the whole appearance.

The small, fine hands, moving sinuously as if direct from the shoulder, serve his rapidly varying tone and mood. Now they lie meekly on the blue-gray trousers, as he graciously compliments Mr. Whitlam on the Labor party’s “struggle” to get back to power in Australia. Now they fly like an actor’s in the air, as he denounces Prime Minister Sato of Japan. Now the right hand is extended, its fingers spread-eagled in professorial authority, as he instructs me to study well a recent editorial in the People’s Daily.

Sitting back in a wicker chair, wrists flapping over the chair’s arms, he seems so relaxed as to be without bones, poured into the chair, almost part of it, as persons seem part of their surroundings in old Chinese paintings. Beside this loose-limbed willow of a man, Mr. Whitlam, hunched together in concentration, seems stiff as a pine.

But the conversation is a freewheeling give-and-take. The Australian style, blunt and informal, fits in well with Mr. Chou’s. The evening has a lively, argumentative note rare in talks between politicians of different countries, rarer still when the countries represent different civilizations. When he disagreed — as on how widespread militarism is in Japan — the Premier would interrupt in English: “No, no, no!” Talking of Australian affairs, he twice frankly said he hoped the Labor party would win the next election in 1972. Occasionally he struck a didactic note. “As you come to China,” he said after suggesting a lesson Australia ought to draw (about the United States) from China’s experience with Russia, “we ask you to take this as a matter for your reference.” Both sides enjoyed themselves making barbs against John Foster Dulles’s policies. The ambience was, in brief, keen and frank.

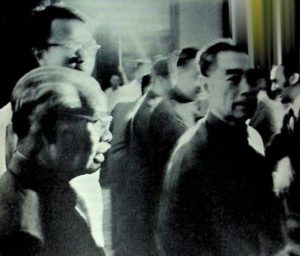

Just before the author was introduced to Chou En-lai, he took this close up of the Premier. On the left is Professor Chang Hsi-jo, head of the Peoples Institute for Foreign Affairs: behind Mr. Chou, and obscured, are the Chinese Ministers for Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade.

Mr. Chou’s aides from the Foreign Ministry and the State Council office had prepared him well. He knew, from reports of what his visitors had said to the Chinese Foreign Minister, that on Taiwan and China’s United Nations seat no great problem existed between Peking and the Labor party. Mr. Whitlam said a Labor government would switch Australia’s diplomatic ties from Taipei to Peking, and vote for Peking’s installation in the China seat at the UN. (Prime Minister McMahon’s regime supported Washington’s unsuccessful “two Chinas’’ proposal in October, 1971.) So the Premier hardly touched these bilateral issues, but instead pitched a complex argument about the overall problems of Asia. (The efficient briefing continued throughout the week. At the evening’s end, Mr. Whitlam happened to recall that his birthday was near. Five days later in Shanghai, the Australian found his birthday observed with a festive dinner and a large cake — tactfully adorned with a single candle.)

Mr. Chou painted a picture of China threatened by three adversaries: the United States, Russia, and Japan. In one way or another, the Chinese press has given this picture ever since November, 1969, when Japan — following the communique signed by Nixon and Sato — seemed to step up to the status of major enemy in Peking’s eyes. Interesting in the Premier’s remarks was the pattern of relationships he sketched between the three adversaries.

After preliminary talk, Mr. Chou reached for his mug of tea, sipped, swilled with deliberation, then asked a question which turned the conversation where he wanted it to go. He was going to be very direct, he warned. What was meant by saying, as the Australians had said the previous day, that the ANZUS treaty (which binds the United States, Australia, and New Zealand in mutual defense) was designed to meet any restoration of Japanese militarism? “That is a special approach to us, so I would like to ask you to inform us what articles or what points of that treaty are directed toward preventing the restoration of Japanese militarism?” Mr. Chou was fingering the apex of Peking’s triangular anxiety.

The Australian background was explained. After World War II, Australia was much less anxious to sign a peace treaty with Japan than was the United States (and to this day Australians are slower to forget Japanese aggression than are Americans). The United States signed ANZUS (in 1951) in large measure to reassure an Australia (and New Zealand) still fearful of Japan. This perspective on ANZUS “down under” was shared by all shades of political opinion. The treaty was a purely defensive arrangement, concerned not with Communist revolutions in Asia, but with Japan — the only country that has ever attacked Australia.

The Chinese leaders leaned forward attentively. The Ministers for Foreign Affairs (Chi P’eng-fei) and Foreign Trade (Pai Hsiang-kuo) were present with senior aides, but the Premier did all the talking. “You know, we too have a defensive treaty, concluded one year before the treaty you have.” He recalled with a grim, ironic smile: “That treaty was called the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Aid. And its first article was that the aim of the treaty is to prevent the resurgence of Japanese militarism!”

But what has happened, the Premier asked rhetorically, his eyes and hands now stirring to life. His answer, in a word, was that both Australia’s ally (the United States) and China’s ally (Russia) have gone back on their pledge to forestall any new danger from Japan. He charged that the Pentagon “is considering whether to give Japan tactical nuclear weapons or even something more powerful.” Does not the fourth Japanese defense plan total $ 16 billion, one-third more than the amount spent on the three previous plans put together? The Nixon Doctrine, he noted, turns Japan into “a vanguard in the Far East.” With a shrewd addition to the usual slogan (“using Asians to fight Asians”), designed to make his visitors feel their potential importance, he assailed the doctrine’s motives. “It is in the spirit of using… ‘Austro-Asians to fight Austro-Asians.’ ”

Then Mr. Chou weighed the actions of the Soviet Union. He never referred to it by name but by sarcastic indirection. “And what about our so-called ally? What about them? They have very warm relations with the Sato government.” Unveiling China’s vision of the world, the Premier wove in two further themes. The Russians, he observed, are also “engaged in warm discussions with the Nixon government on so-called nuclear disarmament.” Now his point came home: “Meanwhile we, their ally, are being threatened by both [Japan, the United States] together!” He finished with an application to Australia’s situation. “So we feel our ‘ally’ is not so very reliable. Is your ‘ally’ so very reliable?

The Premier had a formidable case. He had put it with passion and embroidered it with detail apt for Australian listeners.

It was, Whitlam conceded, a “powerful indictment,” and the Australian took a few moments to marshal himself and probe its questionable parts.

- The first theme had been Japanese militarism.

- The second, the failure of Washington and Moscow to resist it.

- The third, the charge that the United States and Russia are in collusion with each other.

- The fourth, a deep skepticism that any country can really be the ally of any other, an assertion that each country is utterly alone in the world, with nothing but its own resources and its “independence” to gird it.

Throughout forty days in China, these four themes met me at high levels and low. Later there is more to say of each. But stay now with Mr. Chou, for he had a fifth theme in his analysis of the triangle of menace facing China. It was introduced by another of the curious historical analogies he is fond of deploying.

During the talk, Mr. Chou showed a kind of fascination with John Foster Dulles. I remembered with a certain shame what had reportedly happened between these two men at the Geneva Conference in 1954. After lunch one day Dulles walked into the chamber and found only one man there — Chou En-lai. An embarrassing turn of events! Chou held out his hand. Dulles declined it (one account says he murmured “I cannot”), gripped his hands behind his back, and strode out. But this evening Mr. Chou displayed no bitterness, just amusement, at Dulles; and a hearty contempt for his policies. Recalling the circle of defense pacts, multilateral and bilateral, which Dulles made with nations on China’s southeastern borders — and showing accurate knowledge of Dulles’s role as an adviser to the Truman Administration before he became Secretary of State — the Premier mused that it seemed to be an imperative of the “soul” of Dulles to throw a military harness around China. He spoke, I felt, as a man gazing down the corridor of history rather than as one faced with burglars at the door.

Suddenly it became clear that this historical excursion was for the purpose of analogy. He switched to the present. “Now Dulles has a successor,” said Mr. Chou with a laugh that was not a laugh of amusement, “in our northern neighbor.” The Premier was launched in earnest on his fifth theme. Today’s military encirclement of China is by Russia.

This emphasis — that the Dulleses of the 1970s sit in Moscow — was confirmed when discussion turned to present trends within the United States. Mr. Whitlam said that the “soul of Dulles does not go marching on” in America. American public opinion, he judged, would not again permit its government to practice the interventionism in Asia that resulted from the “destructive zeal” of Dulles. Mr. Chou responded: “1 have similar sentiments to you on such a positive appraisal of the American people.” By implication, he agreed that Dullesism was now eclipsed in the United States.

Later he spoke admiringly of the strength of antiwar feeling from coast to coast in the United States (“Even military men on active service and veterans have gone to Washington to demonstrate”). He frankly revealed the source of his confidence about the future course of U.S. policy: “The American people will force the American government to change its policies.” Casting around the room, Mr. Chou asked if his visitors had “in the past two years or so” been in the United States. They had. He then summed up with heavy stress: “So you realize from your own experience that in these past years the American people have been in the process of change.”

Of course, the Chinese Premier disapproves of particular current U.S. actions in Asia; his words on Indo-China made that quite plain. But when he mapped trends, the United States did not seem to loom largest among his concerns. And when he analyzed the dynamics within the triangle of threat, the United States was evidently not the ultimate focus of opposition. He lashed Washington less for its own activities than for its support of Japanese activities and for its collusion with Russian activities.

Caution would be wise in construing what Mr. Chou said. Maybe the three threats to China are so diverse in character that comparing their magnitude is invalid. The Japanese threat is “rising.” The Russian threat is “immediate” in a crude military sense. The U.S. threat may yet be the “biggest” if the three were to be measured objectively against each other at the present moment. A conversation cannot give systematic finality to this caldron of slippery variables. Nevertheless, it was all very different from what Peking was saying in 1964 or even two years ago. Here was a picture of the world that featured power more than ideology, fluid forces more than rigid blocs, emerging problems more than well-worn problems.

Recall that the Premier was talking to Australians, and with an Australian political leader whose views on Taiwan were not opposed to his own. So the two chief bones of bilateral contention between Peking and Washington — the UN seat, the U.S. military presence in Taiwan — did not even come into the conversation. Maybe Mr. Chou calculated that of the three threats to Chinese security, Japan was the one to stress to these visitors. The Russians are far from Australia. The American tie is intimate, and no Australian leader is about to break it. Japan, however, is both important to Australia and a country about which Australians have ambivalent feelings. Yet it was remarkable that Mr. Chou did not raise — nor did his Foreign Minister the previous day — queries about the substantial and sensitive American bases (some related to nuclear weaponry) that dot Australia. Mr. Whitlam told me he had expected — as I had — that the Chinese would harp upon these bases.

It was easy to see that Japan was in the forefront of the Premier’s mind. Whichever country came up, he linked it somehow with Japan. He quoted the Japan Socialist party to buttress his point of view. Broaching the subject of nuclear weapons, he seemed more worried by potential Japanese weapons than by existing massive American and Russian stockpiles. Discussing the Australian Labor party’s international connections, he wondered in particular if it was close to the Japanese socialists. Should not Mr. Whitlam, when he left China for Japan — Mr. Chou had somehow unearthed this unpublicized fact of Mr. Whitlam’s itinerary — make a point of having serious talks with the Japanese socialist leaders as well as with Mr. Sato? The Komeito (Clean Government Party) especially kept popping up. Mr. Chou had met with its leaders the previous week (I had traveled into China in their compartment and watched them photograph each other, the train, and the countryside all the way from Hong Kong to Canton). Was it not “quite something for a Japanese, Buddhist, pacifist party” to make the shift it has this year (to a rather pro-Peking position)? Musing on the Labor party’s prospects of winning power in Australia next year, Mr. Chou again brought in the Komeito party, and made a comparison with it. But seeing its inaptness, he diplomatically qualified himself: “Of course it’s different; your party is very near to power.” A few days later, Mr. Whitlam was surprised that the Chinese put on his program a Japanese movie. Entitled Our Navy, it dealt with World War II and its background. The film was not out of the ordinary. But it seemed remarkable that the Chinese chose to show a foreign (military-political) film to a delegation visiting China, and no accident that it was Japanese.

Zhou Enlai at Huairou Reservoir, Beijing. August 30, 1960.

Photo by Du Xiu Xian; reprinted by Central Documentary Press, Beijing.

Further Reading

Zhou Enlai Internet Archive marxists.org

The ending is easy enough to predict: Despite a few twists and turns, Basher Malone vanquishes Trog, who carries Vic Tayback back to hell through the Pepsi portal. And even though this all sounds kinda awful, it’s fun to watch, complete with cheesy sound effects and a weird soundtrack that’s comprised mostly of bass and synthesizer licks. It’s a fun, mindless diversion for wrestling fans and horror aficionados alike and, truth be told, watching the video isn’t a bad way to spend 20 minutes of your life.

The ending is easy enough to predict: Despite a few twists and turns, Basher Malone vanquishes Trog, who carries Vic Tayback back to hell through the Pepsi portal. And even though this all sounds kinda awful, it’s fun to watch, complete with cheesy sound effects and a weird soundtrack that’s comprised mostly of bass and synthesizer licks. It’s a fun, mindless diversion for wrestling fans and horror aficionados alike and, truth be told, watching the video isn’t a bad way to spend 20 minutes of your life.