Stupsi “contemplates” her doppelgänger.

A few weeks ago, our 7 year-old daughter Z. posed one of the most insightful questions I’ve ever heard. Cradling our Lhasanese dog Stupsi and staring lovingly into her eyes, Z. asked, “Does Stupsi know she has a face?” Unwittingly, she’d posed a deeply philosophical query so complex that I didn’t have much of an answer for her. Instead, I told her that she had asked a very smart question and I wasn’t even really sure how to answer it. I felt like my reply was something of a cop-out but the fact of the matter was that, I needed to reflect a bit more on the very idea of it: Do dogs know they have faces?

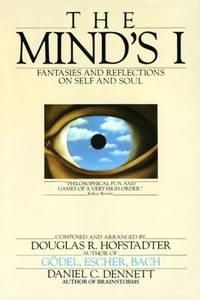

Almost immediately, Z.’s conundrum reminded me of D.E. Harding’s work “On Having No Head,” an essay I’d first read around the age of 17 or so. I was working in a library at the time and in all honesty, I probably spent more time reading books back then as opposed to filing them back on the shelves. I found Harding’s work in The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self And Soul, an anthology of works compiled by Douglas Hofstadter. Indeed, it was the aforementioned essay and Hofstadter’s “Reflections” that followed the piece that would lead to my longstanding affinity for Hofstadter’s work (see another example). And while I still struggle with some of the intricacies of Hofstadter’s writings, he remains one of the most thought-provoking authors I’ve ever encountered and it’s often worth the extra effort to experience his work.

“On Having No Head” is an intriguing piece in which Harding discusses a moment of enlightenment that he once experienced while traveling through the Himalayas:

The best day of my life – my rebirthday, so the speak – was when I found I had no head. This is not a literary gambit, a witticism designed to arouse interest at any cost. I mean it in all seriousness: I have no head.[1]

In total, Harding presents a host of musings in the Cartesian tradition regarding the duality of man’s existence –as both a third party observer of finite surroundings and as an introspective center of being. He continues:

When we observe a couple conversing, we say they see each other, though their faces remain intact and some feet apart, but when I see you your face is all, mine nothing. You are the end of me. Yet…we use the same little word for both operations: and of course, the same word has to mean the same thing! What actually goes on between third persons as such is visual communication – that continuous and self-contained chain of physical processes (involving light waves, eye-lenses, retinas, the visual area of the cortex, and so on) in which the scientist can find no chink where “mind” or “seeing” could be slipped in, or (if it could) would make any difference. True seeing, by contrast, is first person and so, eyeless.[2]

So it’s clear according to Harding that none of us, dogs included, can actually “see” our own faces (if they are, in fact, ever there at all), but what about if a dog – not a person – sees her face in the mirror? Or, what if she is standing face-to-face with another dog? What might she think then?

It’s important to set the framework from humanity’s own relative point of view. Douglas Hofstadter places Harding’s work in the proper perspective to address the original question posed by little Z. In his “Reflections” that follow Harding’s work, Hofstader offers the proposition that self-awareness is the inherent result of life experience and education (although neurological development during early childhood likely plays a crucial role as well), to wit:

It’s important to set the framework from humanity’s own relative point of view. Douglas Hofstadter places Harding’s work in the proper perspective to address the original question posed by little Z. In his “Reflections” that follow Harding’s work, Hofstader offers the proposition that self-awareness is the inherent result of life experience and education (although neurological development during early childhood likely plays a crucial role as well), to wit:

As a child I formulated the abstraction “human being” by seeing things outside of me that had something in common – appearance, behavior and so on. That this particular class could then “fold back” on me and engulf me – this realization necessarily comes at a later stage of cognitive development, and must be quite a shocking experience, although probably most of us do not remember it happening.[3]

Effectively, then, the conversation (the one you’re reading now, that is) comes full circle as Hofsadter himself presents Z.’s query, albeit with a bit more detail and a craftily implied sense of rhetoric:

Do higher animals have the ability to see themselves as members of a class? Is a dog capable of (wordlessly) thinking the thought. “I bet I look like those dogs over there”?[4]

Ultimately, Hofstadter concludes that “the ability to snap oneself onto others seems to be the exclusive property of members of higher species” (my emphasis) in which rational thought and analysis logic trumps instinct or, as Hofstadter himself stats, “logic overrides intuition.”[5] He refers to Thomas Nagel’s seminal work “What Is It Like To be a Bat?” (a portion of which is also offered in The Mind’s I) which remains one of the fundamental discourses on the so-called “mind-body problem.” Nagel’s essay offers further insight into Z.’s original question:

…If the subjective character of experience is fully comprehensible only from one point of view, then any shift to greater objectivity – that is, less attachment to a specific viewpoint – does not take us nearer to the real nature of the phenomenon: It takes us farther away from it.

In a sense, the seeds of this objection to the reducibility of experience are already detectable in successful cases of reduction; for in discovering sound to be, in reality, a wave phenomenon in air or other media, we leave behind one viewpoint to take up another, and the auditory, human or animal viewpoint that we leave behind remains unreduced. Members of radically different species may both understand the same physical events in objective terms, and this does not require that they understand the phenomenal forms in which those events appear to the senses of members of the other species. Thus it is a condition of their referring to a common reality that their more particular viewpoints are not part of the common reality that they both apprehend. The reduction can succeed only if the species-specific viewpoint is omitted from what is to be reduced.[6]

While Nagel, then, argues that it is not possible for humans to comprehend what it is like to be a bat, one might conclude, in a converse sort of analogy, that dogs cannot comprehend what it is like to be a human. As such, a dog would likely not comprehend anything beyond the relatively narrow parameters of his/or her consciousness and perspective.

Donald Davidson’s 1982 essay, “Rational Animals” makes a careful distinction between thought and belief, categorizing the latter as one of a number of propositional attitudes. Propositional attitudes, Davidson asserts, are hallmarks of the kind of rational thought that distinguishes humans from animals.[7]

We identify thoughts, distinguish between them, describe them for what they are, only as they can be located within a dense network of related beliefs. If we really can intelligibly ascribe single beliefs to a dog, we must be able to imagine how we would decide whether the dog has many other beliefs of the kind necessary for making sense of the first. It seems to me that no matter where we start, we very soon come to beliefs such that we have no idea at all how to tell whether a dog has them, and yet such that without them, our confident first attribution looks shaky.[8]

It’s a sad indictment, I’ll admit; reducing the objects of our collective affections to nothing but “dumb animals.” Make no mistake about it: our dogs (and other pets) think, sense and experience all sorts of things…But they process phenomena differently than we human-types do. While recent research regarding American prairie dogs suggests the possibility of social traits well beyond our current understanding of animal interaction but even with such preliminary findings, present perceptions of animal behavior lie somewhere between sterile epiphenomenalism and fantastical anthropomorphism.

I’ll be the first to admit that it’s emotionally rewarding to ascribe all sorts of feel-good niceties to our furry (and not-so-furry) friends, especially when they bring us so much happiness and relief in our day-to-day lives. When we look into the countenances of our pets and experience such tremendous feelings of unconditional devotion and acceptance, the question of who knows what seems of little consequence.

[1] From D.E. Harding’s “On Having No Head” in Douglas Hofstadter’s compilation The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul, pp. 23-33.

[3] From Hofstadter’s “Reflections” on Harding’s work.

[6] From D.E. Harding’s “On Having No Head” in Douglas Hofstadter’s compilation The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul, pp. 391-414.

[7] Similar in concept to the “higher mental functions” elucidated by Vygotsky and others.

[8] From Donald Davidson’s “Rational Animals” in Mind and Cognition: An Anthology, pp. 781-787.