Author: Liu Nung-chao1

Source: People’s China, July 1957; No. 13, p.24-29.

Transcribed/HTML: Mike B. for marxists.org, 2013

Public Domain: Marxists Internet Archive (2013). You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

★

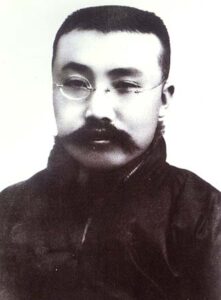

LI TA-CHAO was China’s first propagandist for Marxism and one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party. He was born into a peasant family in Taheito Village, Loting County, Hopei Province on October 29, 1889, six years after the death of Marx and nineteen years after the birth of Lenin. He was a posthumous child and became an orphan as soon as he was born (his mother having died in childbirth). The sole heir to the family fortunes was brought up by his grandparents.

LI TA-CHAO was China’s first propagandist for Marxism and one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party. He was born into a peasant family in Taheito Village, Loting County, Hopei Province on October 29, 1889, six years after the death of Marx and nineteen years after the birth of Lenin. He was a posthumous child and became an orphan as soon as he was born (his mother having died in childbirth). The sole heir to the family fortunes was brought up by his grandparents.

The child grew up at a time when world capitalism was changing into imperialism and the old China was drifting more and more to the position of a semi-colonial and semi-feudal country At eleven, the boy personally saw the atrocities committed by the troops of the eight allied powers on Chinese soil and the heroic resistance put up by the Yi Ho Tuan (“Boxers”) against them. An indelible impression was thus left on his young mind. At sixteen, Li Ta-chao sold about an acre of land, the only property the family had, and with the money enrolled at the Yungping Middle School, Lulung County, Hopei. After a lapse of two years, he left the school and joined the Peiyang School of Law and Politics in Tientsin.

In the 1900s the revolutionary movement was showing signs of fresh power and growth. Between 1905 when it was founded and 1910, the Tung Meng Hui (Revolutionary League), whose leader was Sun Yat-sen, staged seven armed uprisings and grew rapidly. In 1910 spontaneous large-scale revolts broke out in Hunan, Shantung and Yunnan. In the same year, Japan annexed Korea; clearly the spearhead of aggression was now turned towards China.

A Staunch Revolutionary

In 1911 the tide of the democratic revolution swept through north China, and anti-imperialist and anti-feudal ideas began to take root in the mind of the young student. Li Ta-chao not only hated intensely the despotism which condemned the people to a miserable life but also firmly opposed the evils inherent in feudal monarchy which had inflicted untold sufferings on the people for thousands of years. He resolved to join the Tung Meng Hui (Revolutionary League) after the example of his teacher in the Peiyang College,Pai Ya-yu. The neighbourhood of his native county, Loting, was his sphere of activities. There he urged units of the New Army to take revolutionary action.2 On October 10 the Wuchang Uprising which toppled the 2,000 year-old autocratic monarchy erupted. In November the New Army units stationed at Luanchow staged a revolt which was planned by Pai Ya-yu and Li Ta-chao. The uprising was a failure but it nevertheless gave a lively impetus to the 1911 Revolution as it occurred in Chihli Province (the present- day Hopei) where the Manchu court was strongest.

Activities Against Yuan Shih-kai

In 1912, Yuan Shih-kai, boss of the Northern Warlords, took advantage of the revolutionary gains and engineered his election to the provisional presidency of the young republic. The Tung Meng Hui, now reorganized as the Kuomintang, became more and more demoralized with every passing day. Li Ta-chao was angered by the situation and commented on the outcome of the revolution in these words. “The democratic government as it is today is the dictatorship of a handful of violent and crafty scoundrels, it is not a government of the people. The people have been robbed of their rights by a group of these scoundrels and can claim nothing. All the benefit goes to these scoundrels, and the people have nothing at all.”

In 1913 Sung Chiao-jen, one of the leaders of the Kuomintang, was assassinated on the orders of Yuan Shih-kai who was trying his utmost to strengthen his dictatorship. The Yen Chih (Statesmanship), a monthly in Tientsin, carried articles by Li Ta-chao which attacked Yuan in a most outspoken manner. Towards the end of the same year, the situation compelled Li to take flight and seek refuge in Japan. The following year, he entered Waseda University in Tokyo where he studied politics and economics and at the same time continued his activities against the regime. In 1915, the dictator gave in to the Twenty- one Demands of the Japanese Government. These demands, if enforced, would have brought China under Japanese suzerainty. Li Ta-chao travelled all over Japan, calling upan the Chinee students there to rise and fight against the notorious demands. On the suggestion of his fellow students, he drafted “An Open Letter to Our Countrymen” which gained a wide circulation in China, evoking a response even among school children in rural areas. In 1916. Yuan went a step further in his treachery by declaring himself emperor of China. Li Ta-chao immediately returned to Shang-hai, established contacts with various groups and prepared the organization of armed forces for a punitive expedition against Yuan. The nationwide support for the march on Peking finally compelled Yuan to give up his kingship, and he died not long afterwards.

After this victory Li Ta-chao returned to Peking which became the base of his revolutionary activities in the ten years that followed. At this time Peking was the centre of the new cultural movement which made feudalism its enemy and was spreading throughout the country. The soul of the movement was the Hsin Citing Nien (New Youth) magazine. Li Ta-chao was a member of its editorial board and published his famous philosophical article “Youth” in the first number of Volume Two, which appeared on September 1, 1916. This was the first article to appear in modern China which interpreted the universe and human life on the basis of dialectical materialism. Li Ta-chao ended his article with this challenge: “What the Chinese youth should say most solemnly to the world is that it must stop arguing why the old China will not perish but that it should work untiringly for the rebirth of a young China.”By this time, Li Ta-chao had become known as a prominent scholar who had earned the respect and love of the country’s youth. In 1917, at the age of 28, he was appointed to a professorship at Peking University and also as its librarian.

The October Revolution

In 1917 the October Revolution triumphed in Russia, and the imperialist powers launched a cruel war of intervention against the Soviet state. In May 1918 Japan took advantage of the opportunity to work secretly with Tuan Chi-jui, leader of the Anhwei faction of the Northern Warlord group, then in occupation of Peking, to conclude with him so-called military and naval agreements. In the same month more than 2,700 Chinese students in Japan suspended their studies and returned to China to join the fight against the secret agreements. Some of them met in Peking and staged a demonstration under Li’s personal guidance.

From the very first, Li Ta-chao expressed his fast friendship for the young soviet state and pledged all support for it. In an article on the October Revolution, written for the July 1 issue of the Yen Chih, he pointed out: “Civilization after the early days of the twentieth century will surely grow out of today’s Russian revolution…Let us hold our heads up and greet the dawn of the world’s new civilization, let us hearken to the news coming from the new Russia of freedom and humanity!”

Spreading Marxism

Meanwhile, Li Ta-chao invited some young men who were rather more aware of the issues facing the country to form the “Young China Society.” He was also the guide of the “Students’ National Salvation Society,” organized by students formerly in Japan for the continuation of their patriotic anti-Japanese activities. After October 1918 Li got together some able young men from various organizations and founded the “Society for the Study of Marxism” with its headquarters in Peking University Library. “When I worked as an assistant librarian in Peking University,” Mao Tse-tung has said of the period, “it did not take long before I took the road of Marxism under the leadership of Li Ta-chao.” Shortly afterwards, Peking University students founded the Hsin Glum Sheh (New Tide Society) also under Li’s inspiration.

On November 11, the First World War ended. At a mass rally held in the Tien An Men Square in Peking Li delivered a speech entitled “The Victory of the Common People” in which he pointed out that the defeat of Germany was the victory of the masses and the working people. He developed his views further in an article, “Bolshevism’s Victory,” which appeared almost at the same time in the Hsin Ching Niem magazine. “The victory over German militarism,” he wrote, “is the victory of Bolshevism and of the world’s working class; the great achievement is to the credit of Lenin and Marx.” His assessment of the influence of the October Revolution on world history was full of confidence: “It is really impossible for the capitalist governments to dam the onrushing tide…From now on we shall see the flags of victorious Bolshevism and hear its triumphant songs wherever we go. The bell of humanity has sounded! The dawn of freedom is now visible! The world of the future will be the world of the Red Flag!”

In December Li Ta-chao launched a new venture called the Meichou Pinglun (Weekly Review). In an article entitled “A New Epoch,” published in the New Year’s Day issue, 1919, he wrote: “Out of the bloodshed of the 1914 World War and the bloodshed of the Russian Revolution in 1917 has emerged a new epoch. Living in dark China and in deadly silent Peking, we see the first glimmerings of the dawn lighting up the road to a new life. We should seize the opportunity this light offers and march forward and work for the interests of humanity.”

The October Revolution was heartily welcomed by many sections of Chinese society, for their country had tasted to the full the bitterness of oppression by the imperialist powers. However, there were many, including some radical democrats, who were yet unable to appreciate immediately the significance of the October Revolution to the world and the Chinese revolution. But Li Ta-chao was sensitive enough to have observed that it had begun a new epoch for human history and that the Chinese revolution must follow its example. It was this keenness of perception that gave Li Ta-chao his place as the pioneer in modern Chinese history. The radical democrat became a communist.

May the Fourth Movement

On May 4, 1919 the May the Fourth Movement broke out. Li played a leading role in the campaign and dispatched some members of the Society for the Study of Marxism to popularize the movement in several of the larger cities. In the Weekly Review he proposed that the following three principles should guide the course of the movement: (1) Transformation of this robber world, (2) Non-recognition of secret treaties and (3) National self-determination. The movement was thus directed towards a struggle against imperialism and warlord rule. It was a demand for national liberation, democracy and freedom. Thanks to the ideological leadership of Li Ta-chao and other early communists, the events of May the Fourth developed into a great movement to throw out imperialism and feudalism; it began a new era in China.

Only two months after the May the Fourth Movement began, the rapid spread of socialist ideas caused the spokesmen of the comprador bourgeoisie in cultural spheres to come out openly with a call to “stop the tide of Bolshevism.” This led to a major conflict between the communists, with Li Ta-chao at their head, and the bourgeois right-wing represented by Hu Shih. The battle was centred on “Problems and Isms.” In an article “More Study of Problems and Less Talk About Isms,” Hu Shih revealed himself as an opponent of Marxism and a reformist. Hu Shih’s attack was treated to a withering counter- blast by Li Ta-chao. Although many young men had thrown themselves into the struggle against the antiquated culture and its influence, it never crossed their minds that such a fundamental divergence of views could exist among the advocates of the new culture. It was the great debate that opened their eyes to the fact that obsolete bourgeois ideas and nascent proletarian ideas were circulating in their own camp. Where was the new youth of the day heading? They had to make up their minds. The controversy between Hu Shih and Li Ta-chao had the effect of gradually increasing the numbers of those studying and propagating Marxism.

In May 1920 Li Ta-chao organized the first group of Marxists and laid the foundations for the future Communist Party From the earliest days the labour problem engaged the attention of Li Ta-chao. The Weekly Review in the spring of 1919 carried a short article by him about the coal miners’ life in Tangshan, Hopei. Li took a keen interest in the power of the peasants. Before and after the May the Fourth Movement he repeatedly called upon the young people to go to the countryside. After the founding of the Marxist group, propaganda and organizational work was immediately carried out among the workers and Marxism was rapidly linked up with the working-class movement.

After Founding the Party

On July 1, 1921 the Communist Party of China was founded.

Li Ta-chao was put in charge of Party work in north China where he was the guide of progressive students and organizer of the railway workers in their struggles under conditions of brutality and immense difficulties. In August 1922 he went to Shanghai and represented the Party in preliminary talks with Sun Yat-sen on the problem of forming a united front. These talks paved the way for Kuomintang-Communist co-operation, which the Kuomintang National Congress approved in Canton in January 1924. At this congress, Li Ta-chao was elected to the five-man presidium and also to the committee examining the Kuomintang statutes and its manifesto. Thanks to this co-operation with the Communists Sun Yat-sen made a fresh interpretation of his “Three People’s Principles”—Nationalism, Democracy and the People’s Welfare— and formulated the Three Policies of alliance with Soviet Russia, co-operation with the Communist Party and help to the workers and peasants. Li’s work contributed greatly towards the rapid progress of the revolution.

In September of the same year, after a visit to the Soviet Union, Li returned to Peking which was under the control of the Chihli group of the Peiyang Warlords. He established secret contacts with General Feng Yu-hsiang in Peking, whose troops had taken part in an armed uprising at Luanchow in 1911, and urged him to throw in his lot with the revolutionary forces. General Feng rewarded his efforts with a coup d’etat in October which expelled the Chihli regime.3 This coup d’etat helped push forward the revolution in the north. In 1925 Shanghai was shaken by the famous anti- imperialist and patriotic May the Thirtieth Movement which rapidly drew in the whole country. The imperialist powers collaborated with the various warlord groups to attack General Feng’s troops in Peking, Tientsin and Paoting. On March 12, 1926, gunboats of the Fengtien warlords with Japanese naval support raided the Taku Bar and clashed with the National Army. On the sixteenth, the Ministers of eight powers including Britain, the United States and Japan threatened the Peking government with a “protest” which demanded the withdrawal of the National Army Incensed by the demand, the citizens and students of Peking called a mass rally which was followed by a demonstration on March 18 in the Tien An Men Square under the leadership of the Communist Party. The demonstrators proceeded to Tuan Chi-jui’s office, where they demanded an immediate rejection of the eight-power ultimatum. The leader of the demonstrators was Li Ta-chao. Tuan Chi-jui replied to the petition with bullets, more than 200 people were either killed or wounded in the massacre in front of Tuan’s office. While organizing the retreat, Li Ta-chao was knocked down by the running crowd. Despite serious head wounds he managed to get up and did all he could to help the injured.

The incident is known as the tragedy of March eighteenth. The next day the Tuan government issued orders for Li’s arrest, but despite the danger, he continued to work underground in Peking dealing with the heavy work thrown up by the revolutionary movement in the north China provinces. Soon afterwards, the Northern Expedition campaign began and put a priority on revolutionary activities in north China. Li Ta-chao continued to remain at his post, although a white terror raged in the city, and rejected all advice to leave Peking.

A Martyr’s Death

On April 6, 1927 Li and many other revolutionaries were arrested by Chang Tso- lin, a Fengtien warlord, who had then seized Peking. Although he was horribly tortured in prison, he continued to spread the ideas of communism. His courage won over some of the prison guards who carried secret messages for him.

The arrest of Li Ta-chao aroused public indignation and there was talk of action for his release. Students, writers, teachers and others made strong demands for the immediate release of Li, whom they described as a “scholar of great moral courage.” The National Army which had then retreated to Shensi also served a warning by sending a telegram to the militarists in Peking. Railway workers in north China planned to storm the prison and liberate Li Ta-chao even at the cost of their lives. However, Li strongly opposed this rash action on the ground that the revolutionary forces must be preserved at all costs.

On April 28 Li Ta-chao and nineteen other revolutionaries were secretly taken to a remand prison in Hsi Chiao Mm Hsiang where preparations had been made to murder them. The weather was turning warm. Li Ta-chao, his hair uncombed and wearing a brown suit, walked to the execution ground, which was enclosed by trees. Raising his head, he saw the gallows and understood that the brutes were ready to kill him. Smiling, he walked on to the platform and addressed the soldiers and policemen who were to witness his death. It was a hero who spoke: “You are all like fish swimming in a saucepan, yet you are stupid enough to do a shameful deed. The great cause of communism will not die simply because you hang me today! We have trained a multitude of comrades and they are like the seeds of red flowers sown all over the country. We believe that the glorious victory of communism will come in China!” Li Ta-chao proudly finished his words, looked at the sky, smiled, then walked calmly to the gallows! He was 38 when he died.

Li Ta-chao’s whole life was one of an unending pursuit of truth. At first, he grew from a patriotic intellectual into a radical democrat. With the May the Fourth Movement he became a Marxist and together with other communists charted a new road for the Chinese revolution.

Li Ta-chao had many of the qualities indispensable to a revolutionary. In an article commemorating Li Ta-chao, Lu Hsun has written. “He made a very good impression on me: he was honest, modest, and reticent.” All his short life he was hard-working and frugal. When he was arrested, all he had was one yuan and a small gold ring.

Notes

1. The author is a professor at Tsinghua University, Peking. As of 1953. —MIA transcriber.

2. The New Army was an imperial armed force formed along modern lines in the closing stages of the Ching (Manchu) dynasty. The revolutionaries made it one of their main fields of activities.

3. The Northern Warlords were mainly divided into three groups: the Anhwei clique under Tuan Chi-jui, the Chihli clique under Tsao Kun and Wu Pei-fu, and the Fengtien clique with Chang Tso-lin as leader. Following Yuan Shih-kai’s death, civil wars were almost continuously waged between the various cliques which were jockeying for power. Feng Yu-hsiang’s troops were originally under Wu Pei-fu’s command. In the autumn of 1924, a great battle was fought between the Chihli and Fengtien groups in north China. When at the Jehol front Feng’s men rebelled and were moved back to Peking where they staged a coup d’etat, ousted “President'” Tsao Kun and joined the Fengtien forces in a pincer attack on the Chihli armies. Wu Pei-fu was defeated and withdrew to the middle Yangtse. Taking advantage of the chaos Tuan Chi-jui, the Anhwei boss, took over the reins of the Peking government and styled himself the “Provisional Chief Executive of the Republic of China.”