Originally written in August 2009;

There was a time when the spectacle of professional wrestling was very different from the pop cultural phenomenon of today. For the better part of the Twentieth Century, the pro wrestling scene in America was something of a patchwork quilt of diverse practices and attractions; a confederation of territories and promotions, all vying for their “market share” of a hungry and devoted fan base. This was the heyday of pro wrestling’s “Old School.”

Wrestling’s Old School didn’t have the bankroll or technological advances to wage a multimedia blitzkrieg. “Merchandising” and “Pay-Per-View” were relatively unfamiliar terms to the industry, as the aforementioned concepts had yet to be applied to wrestling on a large scale well into the early years of the WWF’s ascension.

Wrestling’s Old School didn’t have the bankroll or technological advances to wage a multimedia blitzkrieg. “Merchandising” and “Pay-Per-View” were relatively unfamiliar terms to the industry, as the aforementioned concepts had yet to be applied to wrestling on a large scale well into the early years of the WWF’s ascension.

Ticket sales to live events proved to be the best indicator of wrestling’s bottom line before the rise of merchandising, cable television, and the Internet. Advertising for these events was important as a strong showing at the gate would cover the promoter’s costs and allow for a tidy profit. Local television stations also provided valuable opportunities for promoters to showcase their productions; from the early days of black-and-white television to the pre-cable days of the color console televisions, the spectacle of pro wrestling grew increasingly accessible to dedicated fans and curious observers.

To compare the days of the local wrestling show to SmackDown or Impact is almost like comparing the theater productions of Ancient Greece or Shakespeare’s Globe Theater to Star Wars or Raiders of the Lost Ark. In early theater, actors and actresses had to work extremely hard to convey a broad range and depth of emotions to their audience. They didn’t have laser shows, entrance music, or computer-cued pyrotechnics to augment their performances. The theatrical performers of yesterday had to rely on their talent and instincts to produce the pathos which proved essential to good storytelling. The same was true of the wrestlers who toiled under the hot lights of cramped local television studios and amphitheaters back in the old days.

For a long time, my memories of these days were reinforced only by a handful of audio tapes I made of some television shows (by setting an old Radio Shack tape recorder next to our console television) and a small collection of programs and vintage wrestling magazines. eBay and YouTube changed all that for the better. In recent years, I’ve had the pleasure of reliving the gritty, smash-mouth days of the territories through DVD compilations and Internet clips.

To my mind, the Memphis (or Continental Wrestling Association) scene of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s is one of the best examples of wrestling’s Old School. Whether you call it “Memphis Wrestling,” “Mid-Southern Wrestling,” or just “Championship Wrestling,” this promotion was a hotbed of wrestling activity in its prime, attracting fans and champions from the AWA and NWA promotions to the Mid-South Coliseum to vie for the top of the card.

This was—for all intents and purposes—Jerry Lawler’s promotion; however, the territory itself was controlled by a handful of promoters during this period. The Memphis area was a Mecca of sorts for the top wrestling talents of the day, including Jackie Fargo, Dutch Mantel, “Superstar” Bill Dundee, Austin Idol, Randy Savage, and many others. Watching the old footage of these proverbial “big fish in a small pond” provides a virtual clinic for wrestling aficionados of all ages as the sheer caliber and creativity of the promotion clearly establishes this promotion and this particular window in time as an important rung on the evolution of pro wrestling.

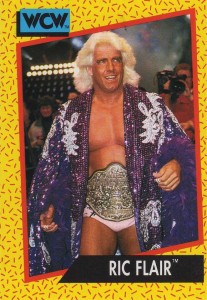

Of all the examples of masterful performances from the Memphis territory, the epitome of this “theater in the raw” might well have come on August 14, 1982. That was the first and only time NWA World Heavyweight Champion Ric Flair came to town to wrestle in the Championship Wrestling studio. Thankfully, I don’t have to rely on my aging brain and increasingly unreliable memory to recreate the action, as a particularly resourceful individual placed the entire episode of this monumental occasion on YouTube. (The Internet is to today’s wrestling fans what “tape trading” was to us just a decade or so ago.)

The dramatis personæ for the aforementioned “mini watershed” event included performers who were both in their youth and at their prime. Lance Russell, who is unfortunately now known best as the man who didn’t induct Jerry Lawler into the WWE Hall of Fame, played his well-established and multifaceted role of narrator, broadcast journalist, and all-around “voice of reason” for what shaped up to be a memorable afternoon at the WMC-TV studios.

Joining Russell to provide important background and context to the event was Promoter Eddie Marlin who had, by this time, established a knack for portraying a semi-impotent figurehead with an uncanny ability to melt completely into the scenery on short notice.

The working premise of Flair’s appearance was multi-faceted: First, there was the notion that an in-studio appearance by the NWA Champion might well “class up” the place, especially given Flair’s larger-than-life persona and second, Flair was slated to wrestle a local jobber during the course of the show, thereby providing local fans with an exhibition of wrestling that was hitherto unseen in the region. Finally, there was a much-anticipated contract signing slated for the show which would guarantee that Flair—as NWA Champion—would wrestle the Southern Heavyweight Champion at some date in the future. Indeed, within a few minutes of the show’s opening and following an introduction by Russell and Marlin, Flair did appear in studio as promised, exuding his uniquely palpable brand of conceit and arrogance. Before Flair could even begin to speak, the WMC studio audience had already decided that Flair was, in fact, a contemptible heel. But once he opened his mouth, folks were not so sure.

Flair’s initial address to the audience threw just about everyone for a loop. Ever the orator Flair showered the audience with backhanded compliments, somewhat confounding the naysayers for the moment. After a few minutes, Ric Flair exited for the dressing room to prepare for his match. For all appearances, this was shaping up to be an interesting, yet forgettable afternoon.

Enter Jerry “The King” Lawler. To paraphrase Jim Ross, business was about to pick up.

Lawler had dominated the Memphis area for years as both heel and babyface and he always made it a point to play each role to the hilt. Flair’s visit coincided with Lawler’s babyface cycle and Lawler exploited the support of his enthusiastic home crowd to his benefit. Lawler, it turned out, was also scheduled to face a jobber on this particular date and, after exchanging a few pleasantries with Russell, Lawler revealed his own agenda for the day: He wanted to personally meet with Flair to extend some greetings and to wish him well…kind of.

Within a few moments, the two men were face to face in before the WMC cameras. For several minutes, the two titans cut a series of “dueling promos” with Lawler playing the devilishly coy hero as Flair matched each wave of babyface wit with his own doses of a crass heel’s overconfidence. Flair—sporting a $7, 000 robe, a Rolex-quality watch and 10 pounds of championship gold around his waist—appeared to be holding his own in a verbal tête-à-tête with Lawler, but the real measure of these men was yet to come. By the end of their epic exchange, hometown hero Jerry Lawler had manipulated the NWA World Heavyweight Champion into giving him and the Memphis are fans exactly what they wanted: Flair versus Lawler live in the WMC studios. Sure, it would be a brief contest…a veritable tease, really. But in the blink of an eye, the entire landscape of the event was altered dramatically when Flair did the unthinkable and agreed to put his championship title on the line. To Flair, the moment was all bravado and the ultimate chance to display his prowess. For Lawler, opportunity was knocking at the door.

What followed was a wrestling exhibition as good as any match in any era. Lance Russell was joined at ringside by his broadcast partner, Memphis television weatherman Dave Brown, and the match was officiated by Jerry Calhoun. Incidentally, Calhoun might well be one of the most underrated and abused referees in the history of pro wrestling. I would be willing to bet that the man has sustained more blows to the head than the combined duo of Sugar Ray Leonard and the Whack-a-Mole game at Chuck-E-Cheese. The man presided over some wild and memorable bouts in his day, for sure.

The ten-minute contest was a mat-heavy affair that featured a fair amount of decent spots for Lawler, who enjoyed the full support of the studio audience. The critical break for Flair came when he managed to dump Lawler out of the ring and on to the studio floor. For the remaining minutes of the match, Ric Flair dismantled a stunned and groggy Lawler, combining of brute force with an arsenal of signature moves to thoroughly subjugate his opponent. With only 30 seconds remaining, Flair went for the coup de grace, placing Lawler in the infamous submission hold known as “The Figure Four Leg Lock.” Victory seemed certain for the gold-maned antagonist, as many lesser men might have tapped quickly in favor of an abrupt and merciful end. But Lawler was cut from a very different cloth and he wouldn’t go quietly. Much like the celebrated submission match between Austin and Hart at WrestleMania XIII some years later, the hero would not yield.

As Lance Russell rang the bell to mark the expiration of time, Flair’s heel persona finally broke through to the surface. Indignant, Flair demanded that the match time be extended by five more minutes so he could finish what he had started. Russsell and Calhoun obliged and the bell rang once more as the final chapter of the drama began to unfold.

Flair started strong, but the worm turned quickly as Lawler caught his second wind. As the balance shifted in Lawler’s favor, he put Flair and the audience on notice that things were about to change by sending his most recognizable signal that a comeback was imminent: He lowered the strap on his tights and charged in for the offensive. Now it was Lawler’s turn to show his best stuff, including a pugilistic volley to the head of the NWA champion followed by a diving fist drop. In true heel form, Flair knew he was beaten and made a hasty retreat, rolling out of the ring and heading for the dressing room. Once Calhoun counted Flair out, the bell rang again. The match was over and Lawler claimed victory. Moreover, he claimed the NWA title. Would the victory stand? Well, of course not. But what remained was something far more important.

Promoter Eddie Marlin returned to ringside for the dénouement, explaining that the match was not officially sanctioned as a title match (per the words of the champ himself) and, as such, the belt could not change hands. Lawler could certainly count this as a moral victory, but nothing more.

When Flair returned to berate Marlin one last time, he brought an important ally with him: the one and only Jimmy Hart. As manager of the reputed “First Family,” Hart’s reputation as the bane of Lawler’s existence made him the most hated of men in the Memphis area. In Hart, Flair had found a valuable ally and (as Flair himself explained to Russell, Marlin, and wrestling fans everywhere) it was Hart who would do Flair’s bidding in the territory from this day forward. Flair sealed the deal by cutting a personal check to Hart in the amount of $10,000; a cash incentive for Hart to bring Flair “the blood…and the sweat…and the guts of Jerry Lawler.” In one fell swoop, Flair transferred a heaping dose of white-hot heel heat on to the local villain before sweeping out of town to return to the big time.

In roughly 45 minutes’ time, these two performers—Flair and Lawler—delivered the kind of compelling performance which might take the large-scale sports entertainment conglomerates of today somewhere in the neighborhood of weeks or months to perfect. Their slow-handed, back and forth crescendo was punctuated not with music videos, product placement, or celebrity star power but with the theatrical skill that even the most skilled of thespians struggle to harness in their finest performances.

The day that Ric Flair visited the WMC studies didn’t just make for a good bit of television on a lazy Sunday afternoon. The entire episode, start to finish, was a full-scale tour de force of the very stuff that carried both Flair and Lawler into the WWE Hall of Fame. They did it with grit, with passion and—most importantly—with pathos, playing their roles like the very fate of nations rested upon their shoulders.

Why?

Because that, friends, is how it’s done.

Many thanks for YouTube user GShea for posting the Flair/Lawler series on the ‘net.

Watch the above-noted series on YouTube:

Memphis Wrestling: Jerry Lawler vs. Ric Flair – Part 1

Memphis Wrestling: Jerry Lawler vs. Ric Flair – Part 2

Memphis Wrestling: Jerry Lawler vs. Ric Flair – Part 3

Memphis Wrestling: Jerry Lawler vs. Ric Flair – Part 4