Presented here is an excerpt from The Theory of Communism: An Introduction, by George Hampsch. Although this section endeavors to summarize Marx’s theory of historical materialism, the writing also includes noteworthy comments regarding Marx’s position on the concept of “human nature.”

★

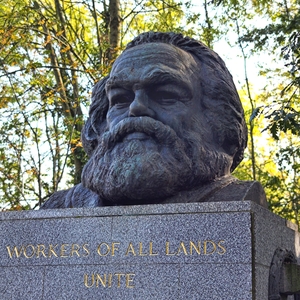

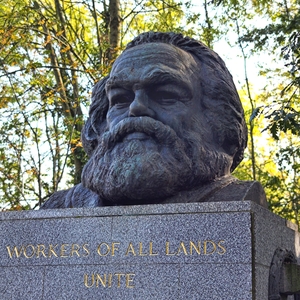

Marx’s grave at Highgate Cemetery in London

Marx’s theory of history was not meant to be a mere speculative hypothesis, a prophetic revelation, or just an opportunist weapon in the hands of revolutionaries. It was, for him, the practical, scientific generalization of laws flowing from the investigation of historical facts. It was to be the statement of scientifically derived laws governing the process of social evolution, laws to be observed in the transformation of human nature from one historical epoch to another. The cornerstone of the theory is this. Men make then- own history, and yet, in another sense they do not make their own history because they do not do so spontaneously under conditions they themselves have chosen. They make history upon terms already determined and handed down to them.

As Engels puts it:

… we have seen that the many individual wills active in history for the most part produce results quite other than those they intended — often quite the opposite; their motives therefore in relation to the total result are likewise of only secondary significance. On the other hand, the further question arises: What driving forces in turn stand behind these motives? What are the historical causes which transform themselves into these motives in the brains of the actors? [30]

These historical causes are represented in the inner laws of the economic development of mankind. Of all the factors determining historical development, the decisive element is pre-eminently the production and reproduction of life and its material requirements. The first premise of human existence and, therefore, of all history is that man must be able to live in order to make history. The first historical act is hence the production of the means to satisfy these essential needs. Economic necessity is the foundation upon which all other parts of the social structure must be built. The ultimate determinant of social change is to be found in the mode of production and exchange of material necessities by which men live. Economics is the foundation or the substructure of society on which a superstructure of laws and political institutions is based, as well as philosophy, art, literature, morality and religion. The entire superstructure of a society is the result of the economic methods of production in use at that time.

In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material forces of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society — the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the social, political and intellectual life processes in general. [31]

History shows this to be true, claims Marx. Feudal society, for example, transformed all its institutions to suit its economic needs. Law was such as to fix men into a landholding system which revolved to the benefit of landlords. Even the Church adopted itself to the economic needs of feudalism. Instead of being the prophet of equality, it neatly adjusted its doctrines to the social hierarchy feudalism needed. As medieval society declined, the merchant class arose and with it a state which in its law emphasized the inviolability of private property. Little by little it cleared away the concepts and institutions which were part of the medieval social structure and replaced them with others built upon the notion of contract. The individual took on new importance. This was reflected in the sphere of religion as well as politics. Protestantism, with its emphasis upon the individual and his conscience as the legitimate spiritual authority, replaced Rome. Se petty sovereignties gave way to the concept of nationalism, because a national government was better suited to help commerce by the promotion of order and legal simplicity. And so on, throughout every age, the student of history finds not a free flow of human events, but concrete necessities set by an economic environment which makes them inevitable. “It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.” [32]

Though the production of the means of life, “the economic base,” is the decisive factor in historical movement and social transformation it is by no means for Marx and Engels the only element operating causally. Political, juridical, philosophical, religious, literary, artistic development is based on economic development, to be sure. But all these also react upon one another as well as on the economic base itself. It is not as though the economic mode of production is the only active cause while everything has only a passive effect. Rather, there is an interaction on the basis of economic necessity, which ultimately must assert itself. [33]

The economic situation is the basis, but various elements of the superstructure… also exercise their influence upon the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their form. There is an interaction of all these elements in which, amid all the endless host of accidents… the economic movement finally asserts itself as necessary… there are innumerable intersecting forces, an infinite series of parallelograms of forces which give rise to one resultant — the historical event. [34]

At each stage of history one finds in it a sum of productive forces, historically caused relations of individuals to the environment and to one another which are handed down to each generation from the previous one. These relations are indeed modified by the new generation, yet they at the same time prescribe the conditions of life, and determine the special character of their further modification and development. Men are products of circumstances. Yet it must never be forgotten that these circumstances are the result of previous generations of men and their activity, and that these very circumstances will themselves be changed by men. [35] Thus, the Marxian concept of history is basically this. Man changes history and is thereby himself changed. All history, then, is nothing other than a continual transformation of human nature. [36]

Ludwig Feuerbach

Throughout their numerous writings, Marx and Engels engaged in considerable analysis and dissection of economic production in order to demonstrate that humanity, in any one historical period, is ultimately determined by the mode of production present in that particular epoch. Yet because historical materialism is above all an ideology, and hence a philosophy of action (praxis) [37] Marx is primarily interested, not in why man can in abstraction be said to be what he is, but rather in why concretely he changes within the progression of history. [38] Since for Marx, human nature in any period is determined by the underlying mode of production, it follows that the concrete changes in man can only be referred ultimately to the concrete sequences of change in the modes of production.

The ultimate determinant of human behavior, and hence the primary conditioning factor in the transformation of human nature is for Marx, modes of production which are employed in the maintenance of human life. The mode of production is a definite form of human activity, a definite manner of life. [39] In fact it is the central expression of human life. As individuals express their life, so they are. What they are coincides with their production, both with what they produce and with how they produce. The nature of humans thus depends on the material conditions determining their production. [40] If it is true that human nature is determined by the character of its productive activities, then the general conditions of production—that is, the conditions without which production could not take place—are likewise the primitive determinants of man’s nature. For Marx, human nature is not an abstraction inherent in, or assigned to, each single individual. For him it is, rather, the ensemble of all social relations that constitutes the human essence in any historical epoch. [41] Yet it should be remembered that Marx did not reduce human nature just to this class nature. He made a distinction between constant “fixed drives which exist under all circumstances and which can be changed by social conditions only as far as form and direction are concerned” and “relative drives which owe their origin to a certain type of social organization.” [42]

A mode of production may be said to be composed of the “factors of production.” These are four in number. Naturally, production presupposes the existence of a needful organism, that is, it presupposes a subject of production, mankind. [43] This then is to be the first factor in the process of production. Since production is essentially an activity carried on for the satisfaction of human wants, it also presupposes the existence of that which is needed, viz., “the object, nature.” [44] Production then is the fitting of natural substances to human wants. Thus a second condition of production, and one which, along with human needs, serves as an instrument in determining the particular mode of production is the character of the natural environment in which the needs arise. The way in which men produce their means of subsistence depends primarily on the nature of the actual means they find in existence and have to reproduce. [45]

If the subject, mankind, involves externally a relation with nature in determining its production, it likewise involves within itself a relation that can properly be called “social,” i.e., a relation involving mutual and cooperative human activity toward an end. [46]

In production, men not only act on nature but also on one another. They produce only by cooperating in a certain way and mutually exchange their activities. In order to produce, they enter into definite connections and relations with one another and only within these social connections and relations does their action on nature, their production, take place. [47]

For Marx, as for Aristotle, man is a zoon politikon, a social animal. All production is an appropriation of nature by the individual only within and through a definite form of society. Since the social relations described constitute an element of production which in its turn delimits the nature of individuals, Marx does not hesitate to conclude that man is an animal which can develop from organism to individual only in society. [48] True production by an individual outside the forces of society would be as great an absurdity as the idea of the development of language without community life and communication. [49] Production is social, man is social, the myth of the social contract and the laissez-faire economists notwithstanding. [50]

This social relation no less than the relation to natural environment is a condition of production, and hence, in its own particular way, a determinant of human nature.

A fourth and final condition of productive activity is the instrument of labor. The instruments of labor comprise the realm of tools and industrial technique. They are, for Marx, that “… which the labourer interposes between himself and the subject of his labour, and which [serve] as the conductor of his activity.” [51] As such, they join the human being to nature and, secondly, through them his activity is transferred to nature. [52] Nature’s material becomes adapted to the needs of man; labor and nature become identified in a product. [53] Human labor has incorporated itself with nature: “the former is materialized, the latter transformed.”

Tools and technique, however, likewise serve to separate man from direct contact with nature. It is the instrument of labor that man directly controls and manipulates, not nature; it is the tool that acts on nature. [54] In this sense, tools can first be said to separate man physically from the object of his work.

In another aspect, too, there is a separation of man and nature. Most instruments of labor, being neither a gift of nature, nor inventions of the immediate users, nor even the direct creative manipulation of nature by any one generation of workers, [55] are the result of hundreds of labor processes that lie between them and nature, from whence sprung their raw material.

For Marx and Engels, these four factors are the structural components of the production process wherever, ehenver and in whatever form it historically appears. These two factors, human labor and its social milieu constitute the subjective side of the process. On the objective side, the other two factors, the natural object of labor, and the instruments, together compose for Marx, “the means of production.” [56] Speaking in the abstract, these four general conditions of production – labor, its social organization, its instruments and its object—are all co-responsible but, may, in differing circumstances exercise unequal causality. [57] Which factor is dominant cannot be decided a priori, but is to be found only through empirical and historical investigation. Any attempt to generalize or predict conclusions in this area is a misconstruction of the productive process. [58]

Yet it can be known a priori that the relation between the factors is one of interdependence, interaction and mutual transformation. For the Marxist knows in advance that humanity will both modify and be modified by nature, society and the instruments it employs, and that each of these and the processes which involve it with human nature will acquire its specific characteristics from the character of the total historical milieu of which these factors and their interdependent relationships are integral parts. [59]

What conditions must prevail in order that the various changes in the modes of production come about? What took place in the history of man that caused the various modes of production — communal ownership in the primitive ages, slavery in the classical world, feudalism of the middle ages and finally capitalism — to develop and grow each in its turn, only to be supplanted by another? In every case, Marx and Engels felt, a point in the development of the mode of production has been reached when certain subjective factors and certain objective factors have come into conflict within the economic system. This conflict has become so irreconcilable that the only possible outcome is the complete destruction of the system in a sudden revolutionary manner and its replacement with a new one. Up until this point has been reached, these factors have been in opposition to one another, but have by their opposition actually fomented the maximum development and fruitfulness of the productive forces—for no social order ever disappears before all the productive forces in it have been developed. [60] After this point of maximum development has been reached, the opposition ceases to be constructive, the conflict becomes such that there is a complete rupture within the system and its superstructure. Political forms, laws, mores, beliefs and behavior patterns of men are transformed. A new mode of production and a new form of society with a transformed human nature comes into being.

At a certain stage of their development, the material forces of production in society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or —what is but a legal expression for the same thing—with the property relations within which they have been at work before. From forms of development of the forces of production these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an epoch of social revolution. With the change of the economic foundation the entire immense superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed. [61]

Some of the factors of production develop more rapidly than do others. The former, Marx refers to as “the forces of production,” the latter, “the relations of production.” As long as a system of production is in a stage of expanding or progressive development, all the factors of production, the human, the social, the natural and the technical are able to be considered forces of production. As the system becomes senile and approaches its violent end, some of these same factors cease to be forces of production. [62] What are these factors which are no longer forces of production? What are these laggard relations of production? Although the phrase “relations of production” is used ambiguously in the writings of Marx and Engels, the term in this context refers simply to the property relations or the system of ownership of the forces of production which prevails in any one system. It is these property or ownership relations which eventually clash with the forces of production. The forces of production are inevitably more powerful, the restrictive property relations are destroyed and the factors of production appear in a totally new form.

How do these abstractions show themselves concretely in present society? Under capitalism, how and why do the productive forces stand in opposition to property ownership? To the Marxist, the conflict within capitalism can be expressed as one of essential incompatibility between social production and capitalistic or individual appropriation. [63] In the medieval period of the artisan, production was for the most part individualistic. The laborer was responsible for the completion of the whole product from raw material to the finished product. As a rule, the raw material belonged to him; he fashioned this with his own tools by means o f his own labor or that of his family. His ownership of the product as based on his own labor, therefore. The production of the product was relatively individualistic and the ownership rightly belonged to the sole producers. As long as the means of production were owned by their individual users, appropriation of the product could justly remain private. Yet by the very fact of individual ownership of the means of production, the potential development of them was greatly restricted. The only way they could develop and become enlarged into the modern gigantic system of production of the present day was to come under a new system of productive relations which allowed for a great concentration of ownership in the hands of a few. Historically, this was accomplished by the bourgeois revolution and the ensuing capitalistic system.

Under capitalism, the relations of production substituted a highly concentrated for a highly diversified ownership of the forces of production. Moreover, modern production took on a social character. Instruments of modern industry as well as the workers who use them are gathered together in large concentrations, and the division of labor is highly developed. No one man is responsible for the completion of the whole product, but shares responsibility for it with perhaps thousands who are likewise engaged in the productive enterprise. No one can say of the finished product: “This is my product; this is what my labor has fashioned for human use.” No worker can at the termination of the day’s labor appropriate even one article at the end of the assembly line without being liable for theft. And rightly so, says the Marxist, for the production is no longer individual but social.

Under capitalism, the relations of production substituted a highly concentrated for a highly diversified ownership of the forces of production. Moreover, modern production took on a social character. Instruments of modern industry as well as the workers who use them are gathered together in large concentrations, and the division of labor is highly developed. No one man is responsible for the completion of the whole product, but shares responsibility for it with perhaps thousands who are likewise engaged in the productive enterprise. No one can say of the finished product: “This is my product; this is what my labor has fashioned for human use.” No worker can at the termination of the day’s labor appropriate even one article at the end of the assembly line without being liable for theft. And rightly so, says the Marxist, for the production is no longer individual but social.

The contradiction of capitalism lies in the fact that in spite of the social character of production the appropriation is still individual and private. The owner of the instruments of labor continues to appropriate the product as under the artisan system although it is no longer his product, but exclusively the product of others’ labor. [64] The individuals who privately appropriate the product of social labor are often those who contribute little or nothing to the labor process, but in virtue of inherited stock certificates, for example, allow others to perform the tasks of producing and distributing the products they now own. This very contradiction between social production and individual appropriation contributed to the rapid development of man’s economic potential in the early stages of capitalism. And this, of course, was a significant step away from the stifling conditions present under feudalistic economies. Capitalism in the eyes of the Marxist, represents a progressive leap in the history of mankind—a throwing off of the repressive feudal bonds. [65] But now the development has ceased and capitalism is in its death-throes. The relations of ownership have ceased to be forces of production but have become fetters on the further economic development of mankind. Progress has become subordinated, or merely serves as a means to personal advantage and profit. These ownership relations must be destroyed to be replaced by others. Mankind is now ready, claims the Marxist, to complement social production with social appropriation, by which those who produce the products by their combined labor will also collectively own the product as well as the instruments of labor. By means of the complete overthrow of capitalism, a sweeping away of the old conditions of production, man will enter a new era of socialism where each will receive in proportion to his contribution. These conditions will in time gradually give way to a higher stage of communism where each will contribute to the labor process according to his ability and receive according to his needs.

Hampsch, G. H. (1965). II. Marxist Theory of Truth. In The theory of communism, an introduction (pp. 17–26). New York: Philosophical Library.

30. Ludwig Feuerbach, in KMSW, I, p. 458.

31. Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, preface, in KMSW, I, p. 356. Hereafter cited as Marx, Critique of Political Economy.

32. Ibid.

33. Cf. Engels, “Letter to H. Starkenburg, Jan. 25, 1894,” in KMSW, I, p. 392.

34. Engels, “Letters to Joseph Bloch, September 21, 1890,” in KMSW, I, pp. 381-382.

35. Cf. Marx, Theses on Feuerbach, HI, in KMSW, I, p. 472.

36. On this point, see Vernon Venable, Human Nature: The Marxian View (New York, 1945), pp. 28-34. Hereafter cited as Venable, Human Nature.

37. Marx, Theses on Feuerbach, KMSW, I, pp. 471-473.

38. Ibid.

39. Marx and Engels, The German Ideology, ed. R. Pascal (New York, 1947), p. 7.

40. Ibid.

41. Cf. Theses on Feuerbach, VI, in KMSW, I, pp. 472-473.

42. Criticizing Bentham’s utilitarianism, Marx says, “He that would criticize all human acts, movements, relations, etc., by the principle of utility must first deal with human nature in general, and then with human nature as modified in each historical epoch.” Capital, 3 vols. (Chicago, 1909), I, 668n.

43. Marx, appendix to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Chicago, 1904), p. 269. Hereafter cited as Appendix to Critique of Political Economy.

44. Ibid.

45. Marx and Engels, The German Ideology, p. 7.

46. Ibid., p. 18.

47. Marx, Wage-Labour and Capital, in KMSW, I, p. 264.

48. Appendix to Critique of Political Economy, p. 268.

49. Ibid.

50. Ibid., p. 267. See also Engels, Dialectics of Nature, p. 282.

51. Marx, Capital, I, 199.

52. Ibid.

53. Ibid., p. 201.

54. Ibid., p. 199.

55. Ibid., p. 202.

56. Ibid., p. 201.

57. Cf. Venable, Human Nature, Chapter VII, especially pp. 89-97.

58. Cf. Engels, “Letter to Conrad Schmidt, August 5, 1890,” in Marx and Engels, Selected Correspondence, trans. Dona Torr (New York, 1942), pp. 472-473.

59. Cf. Venable, Human Nature, p. 97.

60. Cf. Marx, Critique of Political Economy, preface, in KMSW, I, pp. 356-357.

61. Ibid., p. 356. For a further exposition of the Marxist position on the conflict of ownership relations with other forces of production, see Venable, Human Nature, pp. 104-111.

62. Cf. Marx, Capital, I, p. 400. On this point, also see Venable, Human Nature, pp. 105-107.

63. Cf. Engels, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, in KMSW, I, p. 169.

64. Ibid.

65. Ibid., pp. 165-166. See also Marx, Capital, I, part IV.

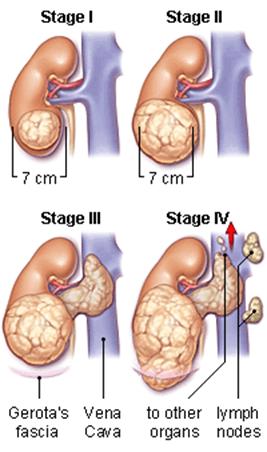

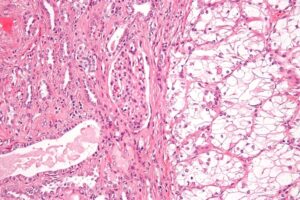

The Orange File” is an irregular series of blog posts through which I will chronicle some of my experiences dealing with a potentially serious kidney issue.

The Orange File” is an irregular series of blog posts through which I will chronicle some of my experiences dealing with a potentially serious kidney issue.

The above information came to me via MyChart at around 4:51 PM on March 17, less than half a day after getting an MRI. The MRI came after a CT scan earlier in the week indicated a mass on my kidney. Working backward a bit further, this all started when I was sent for a CT scan after I went to my doctor complaining of a possible hernia. It all unfolded in, say, about 10 days, from the point of my physical exam with my family doctor to the MRI and subsequent results. So, by most standards, things moved quickly in the grand scheme of things, but seemed to progress agonizingly slowly from day to day. More on that another time.

The above information came to me via MyChart at around 4:51 PM on March 17, less than half a day after getting an MRI. The MRI came after a CT scan earlier in the week indicated a mass on my kidney. Working backward a bit further, this all started when I was sent for a CT scan after I went to my doctor complaining of a possible hernia. It all unfolded in, say, about 10 days, from the point of my physical exam with my family doctor to the MRI and subsequent results. So, by most standards, things moved quickly in the grand scheme of things, but seemed to progress agonizingly slowly from day to day. More on that another time.