On the 27th of July, his sixteenth birthday, Shura announced, "Well, Mum, now you are the mother of two turners!"

Now the children would get up almost before daybreak and come back from work late, but they never complained of being tired. Coming home from the night shift the children did not go to bed at once. When I came home I would find them asleep and the room clean and tidy.

The air raids on Moscow continued. In the evenings we would hear the calm voice of the announcer, "Attention, air-raid warning!"

The words were followed by the screeching of sirens and the threatening roar of locomotive whistles.

Not once did Zoya and Shura go to the shelter. Their coevals—Gleb Ermoshkin, Vanya Skorodumov and Vanya Serov, all three of them fine sturdy young lads, would come round, and they would all go out to keep watch round the house or in the attic. Children and grownups alike were absorbed by the new and terrible event's which had entered their lives, and could think of nothing else.

In the autumn the pupils of the senior grades, Zoya among them, went off to the labour front: the potatoes on a state farm had to be brought in quickly, to save the crop from the frosts.

The frosts had already begun, there had already been snowfalls, and I was worried about Zoya's health. But she was overjoyed at leaving. She took with her only a change of linen, clean notebooks and a few books.

A few days later I received a letter from her, then another.

"We are helping to bring in the harvest. The daily quota is 100 kilograms. On October 2 I gathered 80. That's not much. I will definitely bring it up to 100.

"How are you? I think of you all the time and am worried. I am very homesick, but now I shall soon be back — as soon as we have brought in the potatoes.

"Mummy, forgive me, the work is very dirty and not particularly easy—I have torn my galoshes. But please don't worry, I'll come back safe and sound.

"I keep on remembering you and thinking: no, I am not at all like you. I have not got your patience! Love, Zoya."

I thought for a long time over this letter, and especially over the last lines. What lay behind them? Why had Zoya suddenly reproached herself for lack of patience? There was probably something more in it than that.

When Shura had read the letter that evening, he said knowingly, "I see. She has not been getting on with the others. You know, she often said she lacked your patience, your tolerance towards people. She used to say, 'You must be able to approach people, you must not get angry with them straightaway, and I don't always manage to be like that.'

In one of her postcards Zoya wrote, "I am friends with Nina, whom I told you about." "So Vera Sergeyevna was right," I thought.

One late October evening I returned home a little earlier than usual, opened the door, and my heart missed a beat: Zoya and Shura were sitting at the table. At last the children were with me, we were all together again!

|

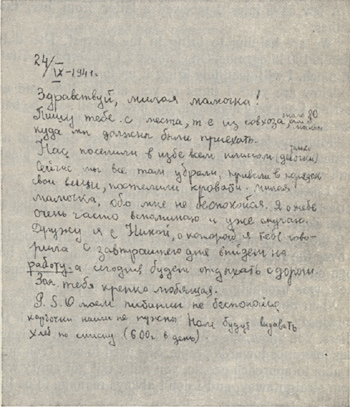

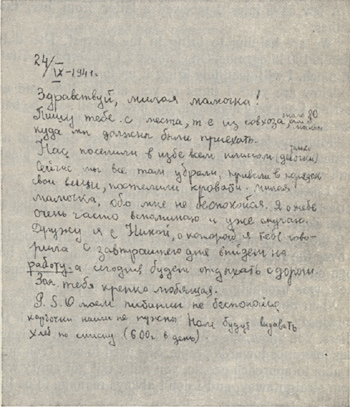

| Zoya's first letter from the labour front. |

September 24, 1941

"Dear Mama,

"Here we are. I'm writing you from the state farm we set out for. It is 80 kilometres from Moscow, The whole of our class (the girls) have been put up in a farmhouse. We have cleaned everything up, put our things in order and are now making our beds. Dear Mama, don't worry about me. I often think of you and am beginning to feet a bit lonesome. Do you remember I told you about Nina? Well, we're always together. Today we're all resting after our journey, and tomorrow we begin work.

"Your ever loving

"Zoya.

"P.S. Don't worry about my food. We don't need ration cards. We'll get our bread (600 grams a day) according to a list that's been drawn up."

Zoya jumped up, ran to the door and threw her arms round me.

"Together again," said Shura, as if he had overheard my thoughts.

The whole family of us sat at the table, drinking tea, and Zoya told us about the state farm. Without waiting for me to ask about the strange lines in her letter she told us this:

"It was hard work: rain, mud, your galoshes stuck, feet were sore. I looked up and saw that three of the boys were working faster than me. They were going on quickly while I kept digging for a long time in one place. Then I decided to find out why it was so. I broke away and began to work on a strip of my own. They took offence and called me an individualist. And I replied, 'Perhaps I am an individualist, but you don't work fair.' You see what was happening: they were working quickly because they were gathering the potatoes only from the top, just for the sake of speed, and were leaving a lot in the earth. But the ones lying deep are the best, the biggest. And I was digging deeply, so as really to dig everything out. That's why I told them they were not working fairly. Then they said to me, 'Why didn't you say so at once, why did you break away?' I answered, 'I wanted to test myself.' And they said, 'You ought to have trusted us more and said so at once…' And Nina said, 'You acted wrongly.' Anyhow, there was a lot of noise and argument." Zoya shook her head in embarrassment and ended quietly, "You know, Mama, I understood then that although I was right I had been lacking in tact. I should have taken it out with the boys first, explained things to them. Perhaps I shouldn't have had to break away then."

Shura gave me a knowing look, and in his glance I read, "I told you so!"

Moscow was becoming more and more tense and watchful with each day. Houses took cover behind camouflage. Orderly detachments of troops marched through the streets. Their faces were worth looking at: tightly pressed lips, a straight steady glance from under knitted brows. Unwavering persistence and a roused wrathful will were plainly written on those facets.

Ambulances raced along the streets, tanks went rumbling by.

In the pitch darkness of the evenings, unrelieved either by the light from a window or from a street lamp, or the swift beam of a car's headlights, one had to feel one's way, carefully and at the same time hurriedly. And with the same hurried cautious steps other people went past, whose faces you could not see. And then air-raid warnings, fire-watching in the yard, the sky torn by ack-ack and sliced by the beams of searchlights and lighted by the purple glow of a distant fire.

It was no easy time: the enemy was closing in on Moscow.

One day Zoya and I were walking along the street, and on the wall of a house we noticed a big placard from which the determined face of a soldier looked at us severely. The keen piercing eyes were looking straight at us, the words printed underneath rang in our ears as if they had been spoken aloud in an urgent voice, "What have you done for the front?"

Zoya turned away.

"I can't pass that placard calmly," she said bitterly.

"But you are still young, and you have been to the labour front—that's also work for the country, for the Army."

"Not enough," answered Zoya doggedly.

For some minutes we walked along in silence, and suddenly Zoya said in quite a different voice, cheerfully and with an air of finality, "I am lucky. Everything I want comes true."

"What are you thinking about?" I wanted to ask, and did not. But my heart was heavy with foreboding.

Next: Farewell, Zoya