The Motherland, bent over her daughter's ashes,

Sings this tender maternal song

About Zoya, the girl, who has become a legend,

Who died and was born for eternal life.

The native land inspired her with courage,

The great nation educated her with pride,

And the girl has become fine as a white birch,

Like the Russian heart, she was frank and noble.

Dimitri Shostakovich

Song for Zoya (1944)

One of the most enduring tales of heroism from the days of World War II is the story of the Soviet partisan Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya. Like the millions of workers and soldiers who joined in the fight against Nazi Germany during the USSR’s Great Patriotic War, Zoya’s life began amidst humble surroundings. But her extraordinary bravery and courage would eventually elevate Zoya to the ranks of the most legendary of Soviet heroes.

One of the most enduring tales of heroism from the days of World War II is the story of the Soviet partisan Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya. Like the millions of workers and soldiers who joined in the fight against Nazi Germany during the USSR’s Great Patriotic War, Zoya’s life began amidst humble surroundings. But her extraordinary bravery and courage would eventually elevate Zoya to the ranks of the most legendary of Soviet heroes.

Zoya was born on September 13, 1923 in the village of Osinoviye Gai (Aspen Woods), situated in the north of the Russia’s Tambov Region. Zoya’s father, Anatoly Petrovich Kosmodemyansky, was a Red Army veteran who maintained the village library and Zoya’s mother, Lyubov Timofeyevna Kosmodemyanskaya, was a school teacher in the village. Two years after Zoya’s birth, Anatoly and Lyubov welcomed another child to their family, Alexander Anatoyevich Kosmodemyansky. Alexander, or “Shura” as he was known to his family and friends, would grow up to be a legendary war hero, just like his sister.

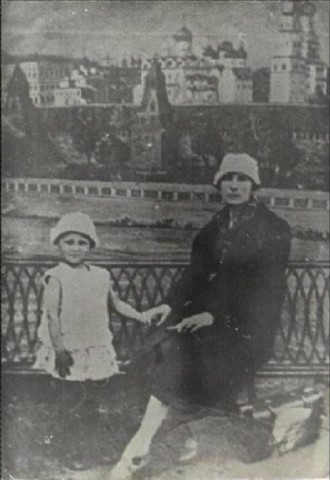

When Zoya and Shura were still very young, their family relocated to the Soviet capital of Moscow. Anatoly worked at the Timiryazev Academy and Lyubov found work as an elementary school teacher. The children were enrolled at the school where Lyubov taught.

From an early age, Zoya was extremely conscientious and attentive to her school lessons. Zoya’s parents instilled within her a keen interest in Soviet life and proletarian culture. According to Lyubov, Zoya excelled in her lessons and her work ethic was profoundly influential on her fellow students.

|

| Zoya (age 3) with Lyubov |

Zoya’s became involved with the Soviet youth movement when she joined the Young Pioneers at age 11. She graduated to the Komsomol (Young Communist League) at the age of 15. Zoya was both diligent and rigid in her adherence to the fundamental tenets of the Soviet youth movement. She followed the doctrines of “clean living” as proscribed by the Komsomol guidelines, including abstinence from use of profanity, alcohol and cigarettes. Zoya’s enthusiasm for political work was extraordinary and her young comrades came to regard her as a role model.

Zoya was 17 years old when her homeland was invaded by the German Army on June 22, 1941. She heard about the attack over the radio and shared the news with her mother Lyubov. Like all Soviet citizens, she was deeply concerned and she wanted to contribute to the fight against the fascist invaders. She continued her political work and joined a fire brigade during the first Nazi bombardment of Moscow. She volunteered at the “labour front,” working at a state farm to harvest crops to feed Soviet citizens and soldiers. But as the fury of the war grew in intensity and as Zoya watched her friends and family leave for the front, she felt obligated to make a greater contribution to the war effort. She became determined to join the fight and to stand shoulder to shoulder with her fellow Soviets as a defender of the Soviet motherland.

Zoya’s upbringing and her experiences within the Soviet Youth movement provided her with a sense of responsibility that motivated her to seek every possible opportunity to make a personal contribution to the war effort. She enrolled in nursing courses in hopes she might be able to assist in the care of wounded Red Army troops, but she was not content to remain in Moscow and study her coursework while the battle raged on at the front lines. She applied to the District Committee of the Komsomol, requesting a role in combat operations at the front. She was granted a personal meeting with the Secretary of Moscow Committee of the Komsomol, and her knowledge, abilities and enthusiasm proved her to be a formidable and impressive candidate to the Komsomol leadership. Two days after her interview, Zoya received her assignment to aid in guerilla operations behind enemy lines. She insisted that her mission remain a secret to all family and friends with the exception of her mother. When she left for the front just a short time later, even her brother Shura remained convinced that Zoya was returning to Aspen Woods to visit their grandparents.

Zoya’s first missions as a partisan fighter were secret and she did not share any details of her work in her correspondence with her mother. Lyubov was deeply worried for Zoya’s safety, but she knew that her daughter was a sensible and strong young woman.

By mid-November of 1941, the German army had driven deep into the USSR. On November 16, 1941, the Germans mounted a new offensive on Moscow. A battalion of the 332nd Regiment, 197th Division, established a camp at the village of Petrishchevo. Zoya’s partisan group harassed and tormented the occupiers by cutting phone lines, destroying bridges and with transport and supply lines. The partisans also performed reconnaissance missions for the Red Army.

On a night in early December 1941, Zoya set out for Petrishchevo as part of a small partisan detachment. Upon reaching the village, Zoya’s comrades remained at lookout posts while she ventured into the village. She cut telephone lines and set fire to a stable which housed the Germans’ horses before rejoining her comrades and returning to camp. Shortly thereafter, she learned that the fire she had set did not fully destroy the building as she had hoped. She was disappointed, but determined to complete her objective. The following night, she returned to Petrishchevo to finish the mission.

Zoya gathered a small kit of benzine and matches and dressed warmly for her nighttime raid. She tucked her hair into her hat and wrapped herself in warm clothes, her youthful femininity disappearing under layers of linen and parka. Accompanying her were two fellow partisans, one of whom served as the commander for the foray into the village. Upon reaching Petrishchevo, the three comrades parted company and set off to complete their individual missions.

Zoya’s mission was to set fire to a stable used by the German commanders to house around 200 horses. Armed with only a pistol, she proceeded cautiously to the perimeter of the building, She gathered kindling at a spot on the outside wall, poured benzene on the small pile and then drew a match and knelt to strike it. But before she could light the match, she was grabbed from behind by a German soldier. She resisted, even attempting to shoot the enemy with her pistol, but she could not escape. Zoya was captured.

The soldier summoned reinforcements who helped to take Zoya into custody. Her hands were bound tightly behind her back and she was taken to the home of some local peasants. She was interrogated by officers and she was tortured relentlessly by her captors who had hoped to gain intelligence that could be used against resistance forces. The torture consisted of some of the most brutal and barbaric acts imaginable, all committed in an effort to extract vital intelligence from the young partisan. Despite severe torture and abuse, Zoya refused to share any information with her captors, identifying herself only by the enigmatic pseudonym “Tanya.” She knew that the fate of her fellow partisans depended on her bravery and perseverance and despite unbelievable pain and misery, she did not betray her comrades to her enemies.

Many hours passed and the Nazis found they could extract no information from her. After a long night of unbearable torment, Zoya was sentenced to execution by her captors the following morning. Her heavy coat and additional outer garments had been confiscated by her captors and she was taken outside wearing only her blouse, trousers and stockings. She was marched through deep snow in freezing temperatures to the village square where a a newly constructed gallows awaited.

Zoya was led to the gallows with a placard around her neck which read “incendiary of homes”. Before she was executed, she spoke bravely to the townspeople who had been rounded up to witness the execution:

Zoya was led to the gallows with a placard around her neck which read “incendiary of homes”. Before she was executed, she spoke bravely to the townspeople who had been rounded up to witness the execution:

“Comrades! Why are you looking so downcast? Be brave, fight, smash, burn the fascists!...I am not afraid of dying, Comrades! It is a great thing to die for one's people!”

…and to her captors, she leveled a warning:

“There are two hundred million of us! You can’t hang us all!”

Zoya was hanged before the villagers that had been forced to witness the spectacle. Her corpse was bayoneted by the Nazis as it hung from the billet. The Germans would not allow the villagers to remove her body for some time after the execution. Instead, they displayed her body as a warning to others who might have considered aiding the partisans. She was buried months later following the beginning of the Soviet counter-offensive.

Zoya’s identity became known over the course of time in the months following her death. She was first identified as “Tanya” by villagers who shared the story with a correspondent from the newspaper Pravda. Zoya’s brother Shura later confirmed her true identity after reviewing Soviet newspaper accounts of Zoya’s execution. Upon reading the newspaper report of her torture and murder, Marshal Joseph Stalin was said to have remarked, “This is what a Soviet girl should be.”

Her body was exhumed from the grave in Petrischevo and she was returned to Moscow for burial. On February 16, 1942, Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was posthumously awarded the title of “Hero of the Soviet Union.” She was the first woman to receive this distinction.

The Germans had documented Zoya’s execution by taking photographs beforehand and afterward. These photos were later found on the body of a dead German officer and shortly thereafter, the rest of the world became eyewitnesses of Zoya's fate. An excerpt from a press dispatch summarized the outrage after the discovery of the photos:

HOW 17-YEAR-OLD ZOYA WAS HUNG BY THE NAZIS — MOSCOW, USSR … “THOSE WHO HAVE BEEN RESPONSIBLE, OR HAVE TAKEN A CONSENTING PART IN WAR CRIMES WILL BE SENT BACK TO THE COUNTRIES IN WHICH THEIR ABOMINABLE DEEDS WERE COMMITTED…THAT THEY MAY BE JUDGED AND PUNISHED.” THOSE ARE THE WORDS OF THE MOSCOW TRIPARTITE PACT, AND HERE WE SEE A SAMPLE OF THE EVIDENCE PILING AGAINST THE NAZIS.

Lyubov Timofeyevna Kosmodemyanskaya, mother of Zoya and Shura, memorialized her children with her book, The Story of Zoya and Shura. Reflecting upon the barbarity of Zoya’s death, she said of Zoya’s executioners:

“…as for them — they are not human. They are not men. They are not even beasts. They are fascists. And they are doomed. Alive they are dead. Today, tomorrow, in a thousand years, their names, even their graves, will be hateful and vile in the eyes of men.”

The German regiment responsible for Zoya’s murder was destroyed by Red Army forces in October 1943. Her brother Shura was involved in the combat operations which crushed the Nazi criminals.

The martyrdom of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya galvanized the Soviet people as they forged ahead in their march to victory against the imperialist juggernaut of Nazi Germany. Her bravery and sacrifice inspired innumerable tributes from all fields and media. The 1944 Lev Arnshtam film “Zoya” tells the story of her arrest and execution. The score for the film was composed by Dmitri Shostakovich. The asteroid 1793 Zoya is named in tribute toher. Monuments to Zoya still stand in St. Petersburg (Leningrad), Tambov, Dorokhov, and Petrischevo.

The martyrdom of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya galvanized the Soviet people as they forged ahead in their march to victory against the imperialist juggernaut of Nazi Germany. Her bravery and sacrifice inspired innumerable tributes from all fields and media. The 1944 Lev Arnshtam film “Zoya” tells the story of her arrest and execution. The score for the film was composed by Dmitri Shostakovich. The asteroid 1793 Zoya is named in tribute toher. Monuments to Zoya still stand in St. Petersburg (Leningrad), Tambov, Dorokhov, and Petrischevo.

Although post-Soviet historical revisionism has included attempts to cast aspersions on the heroic story of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, her life and struggle are still celebrated by many to this day.

The story of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya still stands today as an inspiration in the worldwide struggle against oppression.

Aluta continua!

Mike Bessler, 2005

Revised and expanded November 2008

Read more about Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya in the book Red Youth: Young Heroes of the Great Patriotic War, Volume One from Erythros Press and Media, LLC.

Hindus, Maurice. Mother Russia. Halycion House: New York, 1943

Kosmodemynskaya, Lyubov. My Daughter Zoya. Foreign Languages Publishing House: Moscow, 1942

Kosmodemynskaya, Lyubov. The Story of Zoya and Shura. Foreign Languages Publishing House: Moscow, 1953

"Kosmodemyanskaya, Zoya." (Wikipedia article)

"Review: Shostakovich Soja (Zoya), suite Op. 64a (1944) The Fall of Berlin, suite 82a (1949)" (Music Under Soviet Rule: CDs: Shostakovich films)

Articles and Texts from gammacloud.org

Image Gallery from gammacloud.org

Read the full text of the book The Story of Zoya and Shura by Lyubov Kosmodemyanskaya

Soviet History Archive: The Great Patriotic War from marxists.org

"Kosmodemyanskaya" (Time magazine article/obituary from 1944)

"Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya" (Northstar Compass) warning: disturbing images

"Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya" (Voice of Russia)

Zoya's Story: An Afghan Woman's Struggle for Freedom (Amazon listing)

Articles from Pravda.ru

2001-11-29: 60th Anniversary Of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya's Feat

2002-11-26: Teenage Soviet Hero Executed 61 Years Ago

2003-02-13: Russia's Past Totally Misinterpreted in Modern Books on History

"Song About Zoya" (in Russian) mp3 from SovMusic.ru

St. Petersburg monument photo used with kind permission from Peter Sobolev's Wandering Camera