L. Kosmodemyanskaya

The Story of Zoya and Shura

Together Again

At the end of August we arrived in Moscow. Anatoly

Petrovich met us at the station. The children jumped out

of the carriage almost before anyone, and rushed over to

their father. Then they stopped. After all, they had not

seen their father for a whole year, and of course they felt

awkward.

But Anatoly Petrovich understood their embarrassment. He swept them both up into his arms and, although

he was always restrained and undemonstrative, kissed

the children hard, stroked their short hair, and said, just

as if they had only parted yesterday:

"Well, now I will show you Moscow. Let's see if it's

anything like our Aspen Woods."

We got into a tram—what a bold new experience that

was!—and rode rumbling and clanging round Moscow,

past the tall houses, past motorcars, past the hurrying

pedestrians. The children took in the sights with their

noses glued to the windowpane.

Shura was quite dumbfounded to see such a lot of people in the street. "Where are they all going? Where do

they live? Why are there so many. of them?" he shouted,

forgetting all restraint and arousing smiles among the

passengers. Zoya was silent but one could read the same

eager longing in her face: faster, faster! We want to see

everything, know everything about this huge, wonderful

new town!

|

|

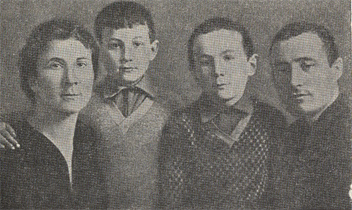

As soon as Zoya and Shura arrived

in Moscow Anatoly Petrovich took them

to the photographer's. "We must have our

photograph taken to celebrate our reunion,"

he said. In the photo (left to right)

are Lyubov Timofeyevna, Zoya, Shura

and Anatoly Petrovich. Zoya was eight then, Shura six |

And at last we reached the outskirts of Moscow, a small

house near the Timiryazev Agricultural Academy. We

went up to the second floor and entered a small room: a

table, beds, a small window. We were home!

Of all the memorable days in the life of a man the

day when he takes his child to school for the first time is

one of the happiest. Probably all mothers remember it. I

remember it too. That 1st of September 1931 was a clear,

cloudless day. The trees round the Timiryazev Academy

were all golden. Dry leaves rustled under our feet, whispering something mysterious and cheering—they must

have been saying that from now on my children would be

leading an entirely new life.

I led the children by the hand. They walked along,

grave and solemn and, no doubt, a little frightened. In

her free hand Zoya had firm hold of a schoolbag, in which

lay an ABC book, notebooks ruled with slanting lines and

squares, a box of pencils. Shura had very much wanted to

carry this wonderful case, but Zoya had got it by seniority. In thirteen days' time Zoya would be eight years old,

and Shura was barely seven.

Of course Shura was very small, but, nevertheless, we

had decided to send him to school. He was very used to

being with Zoya and could not even imagine how it would

be if Zoya went to school and he stayed at home. And

anyway there was no one to leave him with: Anatoly Petrovich and I were both working.

My children's first schoolteacher was myself. I was in

charge of the preparatory grade, and the school principal

sent Zoya and Shura to me.

And so we went into the classroom. Thirty boys and

girls, no bigger than my two children, stood up to meet

us. I put Zoya and Shura on the same bench, not far from

the board, and began the lesson.

In those first days, I remember, one little fellow took

it into his head to hop round Zoya on one foot, singing:

"Zoya, Zoya, she's so thin, she fell into the rubbish bin!"

He bawled out the silly words with real delight. Zoya listened in silence, quite impassively, and when the lad

stopped for a moment to draw breath, she said calmly:

"I did not know you were so stupid."

The boy blinked bewilderedly, repeated his ditty once

or twice, but no longer with the same enthusiasm, and then

left Zoya alone altogether.

Once, when Zoya was monitor, someone broke a window in the classroom. I had no intention of punishing the

offender: I don't think there is a person alive who has

not broken at least one window sometime in his life.

Without that there would be no childhood. Shura, for

one, broke more windowpanes than any other boy of my

acquaintance.

I did not enter the classroom at once, and stood in the

corridor thinking over how to begin talking to the children, and hoping that the culprit would confess of his

own free will. And then I heard Zoya's voice:

"Who broke it?"

I peeped into the classroom quietly. Zoya was standing on a chair, and the children were crowding round her.

"Who broke it? Speak up!" Zoya demanded. "I can

tell by the eyes, anyhow," she added with deep conviction in her voice.

A short silence followed, then Petya Ryabov, with fat

cheeks and snub nose, one of the chief troublemakers of

the class, said with a sigh, "It was me…"

Apparently he really did believe that Zoya could read

most of his secret thoughts in his eyes. She had said it

like that, as if there were not a shadow of doubt about her

ability to do so, but there was, in fact, a very simple story

behind her words. Grandma Mavra Mikhailovna would

always say to her grandchildren when they had done

something wrong: "Who did that? Now then, look me in

the eyes, I can tell everything by looking into your

eyes!"—and Zoya had, remembered Grandma's wonderful

method of discovering the truth.

Soon Zoya and Shura had to be transferred from my

class to another, and this is why.

Zoya behaved herself very restrainedly and never

rubbed in our relationship. Sometimes she even called me

Lyubov Timofeyevna, thus emphasizing that in class

she was the same as all the other pupils, and that for her,

just as for all the others, I was a teacher. But Shura

carried on in quite a different manner. During the lesson,

having waited for a moment of complete silence, he would

suddenly hail me, "Mama!"—followed by a sly look

round.

Shura's sallies usually called forth confusion in the

class: teacher Lyubov Timofeyevna, and suddenly—

mama?! The children thought this very funny, but it hindered their work. And after a month I had to transfer my

children to the teacher in the parallel class.

School and schoolwork gained complete possession of

Zoya. As soon as she had come home and had something

to eat, she would sit down to her homework. We

never had to remind her to do so. The most important and

interesting thing, the thing which occupied all her thoughts

now, was study. She wrote out every letter, every

figure with extreme care, and picked up her notebooks

and exercise books as carefully and lovingly as if they

were alive.

When the children used to sit down to their lessons

Zoya would ask severely:

"Shura, are your hands clean?"

At first he attempted to rebel.

"What business is it of yours? Leave me alone!"

But afterwards he gave up, and before taking hold of

schoolbooks he would go and wash his hands, without

waiting to be reminded. The precaution, I must say, was

a necessary one: after he had been playing with his boys

our Shura usually came back from the yard up to his ears

in mud. Sometimes you just could not understand how he

had contrived to make himself so dirty. It was as if he had

rubbed himself first in sand, then in coal, then in whitewash, then in brick dust…

The children prepared their lessons at the dinner table.

Zoya would sit over her books for hours. Half an hour was

Shura's limit. He wanted to be out in the street with the

boys. And he would keep on sighing and shooting glances

at the door.

One evening he pulled out a bundle of bricks and

matchboxes, and carefully laid them out in a row, thus

walling off one half of the table.

"That's your half, this is mine," he declared to Zoya.

"Don't dare to come over onto my side!"

"But what about the ABC book? And the inkwell?"

asked Zoya in bewilderment.

Shura was not to be put off.

"You can have the ABC and I'll have the inkwell!"

"Stop playing about!" said Zoya severely, and promptly removed the bricks from the table.

But it didn't suit Shura's fancy to prepare lessons

without a bit of fun, and he always tried to turn homework into a game. What could you do about it! After all,

he was not seven yet.

Next: A Holiday