Introductory note: I wrote these essays in 2007 as part of a series for my previous blog. It was intended to be a four-part series, and I actually completed the first three parts. Over the years since I wrote these, I have lost all of the original posted/published versions. The versions below are compiled from my original notes of parts one and three (part two appears to be gone forever). I am reposting these now — in 2020 — as a supplement to a forthcoming podcast project, Rush Strutter Zep Magik.)

Part One: Waxing Philosophical

I have noticed that my interests tend to run in cycles. I have a lot of interests and a lot of “favorites.” Every so often, I might read a whole lot on one particular subject and then, as quickly as my interest builds I shift to another topic. I am like this with modern Russian and Chinese history, reading a spate of books on one over the course of weeks to months, then shifting back to the other, maybe picking up another unrelated interest in between and then returning back to Russian or Chinese history for a stretch. I am the same with comics, television, sports and probably other things. I have never really looked for a pattern or a relationship to seasons or events in my life… It’s just something I have just come to accept. I am especially this way when it comes to music. I will often go for several weeks concentrating on work by one artist or another until my interest shifts to something else. But as quickly as the tide rolls in, it rolls out again and I’m on to something else.

For many, many years now, Rush has been a recurring favorite in my listening rotation. About two or three times a year, I enjoy a steady diet of Rush material, from their earliest days through some of their more recent fare. If I made a soundtrack for a movie about my life, there would certainly be a few Rush songs in there representing some of the better moments of my existence thus far. But as much as I have loved this music over the years, I have grown to have some reservations regarding the philosophy which apparently guides the band. Much of this has come in the last decade or so as I have grown older and more politically aware. Since I am currently in the midst of my semi-annual Rush fixation, I thought this might be as good of a time as any to reflect a little on my affection for the music and my thoughts on the philosophy behind the band. I am sure I don’t have the time or patience to write a thorough exposition and analysis of the philosophical underpinnings of this rock and roll icon. I’m not up to writing an amateur dissertation here — I’m just waxing philosophical. Think of it as “blogging out loud.”

For many, many years now, Rush has been a recurring favorite in my listening rotation. About two or three times a year, I enjoy a steady diet of Rush material, from their earliest days through some of their more recent fare. If I made a soundtrack for a movie about my life, there would certainly be a few Rush songs in there representing some of the better moments of my existence thus far. But as much as I have loved this music over the years, I have grown to have some reservations regarding the philosophy which apparently guides the band. Much of this has come in the last decade or so as I have grown older and more politically aware. Since I am currently in the midst of my semi-annual Rush fixation, I thought this might be as good of a time as any to reflect a little on my affection for the music and my thoughts on the philosophy behind the band. I am sure I don’t have the time or patience to write a thorough exposition and analysis of the philosophical underpinnings of this rock and roll icon. I’m not up to writing an amateur dissertation here — I’m just waxing philosophical. Think of it as “blogging out loud.”

The first Rush song I ever listened to — and I mean really listened to — was “Tom Sawyer.” I’m sure that’s probably true for a lot of people. I was about 13 or 14 and I taped the song off the radio along with some other songs that were apparently rather forgettable. I think I might have been sick and I was home from school on a weekday. I listened to the tape at least once a day for a really long time and the only songs that I really recall from that particular mix were “Tom Sawyer” and “Break on Through” by The Doors (the latter song would lead to a fascination with the doors a short time later). I mean, I am sure I had heard a lot of Rush before that particular day, but to have finally captured a song off the radio was kind of a big deal for me back then. I was really taken by the music (“prog rock” is what they call it, I guess) and the lyrics, the meaning of which was not really clear to me back then (and still aren’t today) was equally captivating.

Eventually, I got around to buying Moving Pictures on cassette and soon after, I got Fly by Night for $4.99 from a K-Mart store. I still remember looking at the big owl on the cover of Fly by Night while I fiddled and fumbled with the removal of the long, plastic anti-theft casing. Whenever I bought tapes back then, I would usually spend about 20 minutes trying to pry the plastic off casing with a screwdriver before I realized that a wire-cutter would get the job done a lot faster. Fly by Night was such a great album. It was years before I appreciated the grandeur of “By Tor and the Snow Dog,” (which happened after I finally listened to the live version on All the World’s a Stage at the repeated urging of a coworker from one of my part-time jobs while I was in high school) but most of the other tracks made strong impressions on me almost immediately. I was already familiar with the title track from one of the local “album rock” (that’s what they used to call “classic rock”) stations and that was all well and good, but “Anthem” (more on the significance of the song’s title later) and “In the End” were favorites of mine. I remember playing “Anthem” for my dad on the way to school one morning and he was less than impressed. Years later, I had Thomai over to my house on a date and I recall sitting in my room and playing “In the End” for her on my electric guitar. I played the soft part intro and then I stood on a chair and turned on the distortion to belt out the heavy part. She was very impressed. I wonder if she still remembers that…

And then there was 2112. This album changed everything in a big way. I don’t remember exactly when I bought it, but I remember listening to it back when I was working a part-time job at a fast-food restaurant, so I would have been 16 or so at the time. I was already familiar with the lengthy, over-the-top masterpieces of Led Zeppelin from albums like Physical Graffiti and Presence. The fact that Zeppelin was able to fill an entire side of “The Song Remains the Same” with just one song, a live version “Dazed and Confused,” had really impressed me. But the song “2112” — lasting a full 20 minutes and 33 seconds and comprising the entire first side of the album— really blew my mind. Of course, this particular song was a story; a truly epic tale for the ages. Most people who are familiar with the album know the gist of the story: A sterile and bland future world ruled by an authoritarian clique is rocked with controversy when a young man discovers a long-forgotten relic. The relic is a guitar which the man tunes and plays happily. In his excitement, he takes the guitar before the rulers and attempts to show them how the music from the guitar can change the world for the better. The rulers dismiss the man and his discovery, and in doing so they dash his dreams for a happy life. Deciding that he cannot live in such a cruel heartless world, the man commits suicide. A planetary war ensues in which the rule of the clique is threatened and the finale, while somewhat ambiguous, leaves plenty of room for one’s active imagination to take it from there.

And then there was 2112. This album changed everything in a big way. I don’t remember exactly when I bought it, but I remember listening to it back when I was working a part-time job at a fast-food restaurant, so I would have been 16 or so at the time. I was already familiar with the lengthy, over-the-top masterpieces of Led Zeppelin from albums like Physical Graffiti and Presence. The fact that Zeppelin was able to fill an entire side of “The Song Remains the Same” with just one song, a live version “Dazed and Confused,” had really impressed me. But the song “2112” — lasting a full 20 minutes and 33 seconds and comprising the entire first side of the album— really blew my mind. Of course, this particular song was a story; a truly epic tale for the ages. Most people who are familiar with the album know the gist of the story: A sterile and bland future world ruled by an authoritarian clique is rocked with controversy when a young man discovers a long-forgotten relic. The relic is a guitar which the man tunes and plays happily. In his excitement, he takes the guitar before the rulers and attempts to show them how the music from the guitar can change the world for the better. The rulers dismiss the man and his discovery, and in doing so they dash his dreams for a happy life. Deciding that he cannot live in such a cruel heartless world, the man commits suicide. A planetary war ensues in which the rule of the clique is threatened and the finale, while somewhat ambiguous, leaves plenty of room for one’s active imagination to take it from there.

At 16 years old, much of the political overtones were lost on me. The theme of the rebellious spirit striking out against feelings of alienation and repression was understandably appealing to me as an angst-filled teenager. The music on the album was a fantastic range of heavy rock, ballad-like interludes, and musical narratives. Even these days, I still listen to “2112” quite often. In fact, “Soliloquy/Grand Finale” is still one of my favorite rock pieces of all time.

My first copy of 2112 was a cassette and the older Rush tapes didn’t include the full liner notes that were available on LP versions. I don’t have the old cassette version anymore, but I am relatively certain that it didn’t have any liner notes at all; just a shot of the main cover image and the track names. It wasn’t until many years later that I picked up 2112 on LP from a secondhand record store on High Street in Columbus. It was then that I held the full gatefold LP cover in my hands and read the words which had gained Rush notoriety in some circles and scorn and infamy in other:

“With acknowledgment to the genius of Ayn Rand”

But who was Ayn Rand and why did it matter?

★

What you own is your own kingdom / What you do is your own glory

What you love is your own power / What you live is your own story

In your head is the answer / Let it guide you along

Let your heart be the anchor / And the beat of your own song

— from the Rush song “Something for Nothing” (lyrics by Neil Peart)

★

Rush Reflections, Part Three: Bravado

Objectivism: Who needs it? As I was preparing to write this article, I gathered a small batch of Rand’s books from my personal library and I laid them out in my computer/writing area. My cousin was over visiting one evening and he picked up some of the books and said, “What are you doing reading Ayn Rand?” I told him I was writing a critique of sorts and I was getting re-acquainted with the subject matter. He turned the books over in his hands a few times and read a few words out loud from the book covers: “Anti-egalitarianism”… “The evils of altruism” … “What else do you need to know?” he asked. Well put, indeed.

Objectivism is an ugly philosophy. The proponents of Objectivism – the “Objectivists,” if you will – have written scores of volumes in celebration of this purportedly “brilliant” epistemology that celebrates the “noble” practices of individualism, greed, and selfishness. Extensive and coherent critiques of Objectivism are, at least in my experience, a bit harder to come by. I have noticed that Objectivist rhetoric often provokes an incredibly emotional response from its detractors and perhaps it is the visceral emotional reaction of opponents which ultimately precludes opponents from effectively refuting the most basic of Randian tenets. It’s certainly not my intent to craft some sort of scholarly repudiation of Randian thought but I do want to take a very brief look at what makes Objectivism so objectionable. Of course, one of the best places to start with such a critique is by perusing Rand’s smaller works, such as her writings from her newsletter, “The Objectivist.” Since Rand quotes herself quite often, she often provides specific key references from her larger works in her essays. To put it succinctly, one can get a good impression of Rand’s general philosophy without suffering through large tomes such as Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead.

Objectivism is an ugly philosophy. The proponents of Objectivism – the “Objectivists,” if you will – have written scores of volumes in celebration of this purportedly “brilliant” epistemology that celebrates the “noble” practices of individualism, greed, and selfishness. Extensive and coherent critiques of Objectivism are, at least in my experience, a bit harder to come by. I have noticed that Objectivist rhetoric often provokes an incredibly emotional response from its detractors and perhaps it is the visceral emotional reaction of opponents which ultimately precludes opponents from effectively refuting the most basic of Randian tenets. It’s certainly not my intent to craft some sort of scholarly repudiation of Randian thought but I do want to take a very brief look at what makes Objectivism so objectionable. Of course, one of the best places to start with such a critique is by perusing Rand’s smaller works, such as her writings from her newsletter, “The Objectivist.” Since Rand quotes herself quite often, she often provides specific key references from her larger works in her essays. To put it succinctly, one can get a good impression of Rand’s general philosophy without suffering through large tomes such as Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead.

So there’s a lot of written material to choose from, but it’s even more compelling to hear Rand’s thoughts from Rand herself. YouTube offers a series of interviews with Ayn Rand, including a vintage episode of the Mike Wallace Show from (1959) and an episode of the old Donahue show from (1979) (It’s worth noting that the user comments feature is disabled on all of the Rand interview pieces). I have read numerous works by Rand over the years, but when I discovered the Wallace interview on YouTube recently, I was once again struck by the ugliness of Rand’s world view. Hearing the venom pour from her own lips really puts her writings in a better perspective. In one segment, Rand answers Wallace’s request to explain the fundamental tenets of “Randism.” Rand corrects him and refers to her philosophy as “Objectivism” and explains:

My morality is based on man’s life as a standard of value. And since man‘s mind is his basic means of survival, I hold that if man wants to live on earth and to live as a human being, he has to hold reason as his only guide to action and that he must live by the independent judgment of his own mind. That his highest moral purpose is the achievement of his own happiness, and that he must not force other people nor accept their right to force him. That each man must live as an end in himself and follow his own rational self-interest.

Of course, nobody wants to be “forced” to do anything. So, I respectfully submit that Rand’s use of the word “force” is something of an inflammatory red herring. The real issue is not of “forcing” morality, per se, but one of fostering empathy and commonality. Rand says these things are inherently counterproductive and immoral. Simply put, in Rand’s world self-gratification is paramount. To hell with everyone else.

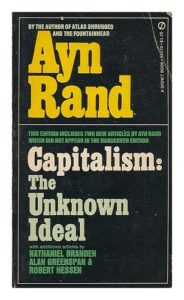

Capitalism, The Unknown Ideal presents one of the clearest pictures of Objectivism as ideology; a time and place in which unbridled, unregulated capitalism reigns supreme and the wants of the individual supersede the needs of the masses. It is, at the most basic level, concentrated elitism which builds its arguments upon a marriage of idealistic self-promotion and incomplete, self-serving critique on a multitude of topics. It is in this particular work that Rand declares capitalism to be “only rational and moral system in man’s history” (p. 34; all references to this text are from the 1967 Signet paperback edition). A brief look at statistical data from capitalist countries around the time of this essay puts Rand’s declaration in a proper perspective. In Ernest Mandel’s Introduction to Marxism, Mandel provides an overview of social inequality in a capitalist society, circa 1973. It’s hard to imagine these compelling figures as being indicative of a “rational and moral system.”

Capitalism, The Unknown Ideal presents one of the clearest pictures of Objectivism as ideology; a time and place in which unbridled, unregulated capitalism reigns supreme and the wants of the individual supersede the needs of the masses. It is, at the most basic level, concentrated elitism which builds its arguments upon a marriage of idealistic self-promotion and incomplete, self-serving critique on a multitude of topics. It is in this particular work that Rand declares capitalism to be “only rational and moral system in man’s history” (p. 34; all references to this text are from the 1967 Signet paperback edition). A brief look at statistical data from capitalist countries around the time of this essay puts Rand’s declaration in a proper perspective. In Ernest Mandel’s Introduction to Marxism, Mandel provides an overview of social inequality in a capitalist society, circa 1973. It’s hard to imagine these compelling figures as being indicative of a “rational and moral system.”

A pyramid of wealth and social power exists in all capitalist countries. In the USA, a Senate Commission has estimated that less than one percent of American families possess 80per cent of all shares in companies and that 0.2 percent of families possess more than two-thirds of these shares. In Britain, in 1973, the richest one percent of the population held 28 percent of all marketable wealth; and the richest five percent, 50.5 percent of that wealth (these figures, however, strongly understate the concentration of wealth because they include private dwellings which, for a large part of the population, are not ‘marketable wealth’ but necessary living conditions). In Belgium one-third of the citizens are at the bottom of this pyramid, possessing nothing other than what they earn and spend, year in, year out; they have no savings and no assets. Four percent of the citizens occupy the top of this pyramid, owning half the private wealth of the nation. Less than one percent of Belgians own more than half the stocks and shares in the country. Among these, 200 families control the big holding societies which dominate the whole of the nation’s economic life. In Switzerland, one percent of the population possess more than 67 percent of the privately-owned wealth.

Inequality of revenue and wealth is not only an economic fact. It implies inequality in chances of survival and death. In Great Britain before the Second World War, the infant mortality rate in the families of unskilled workers was double that in bourgeois families. Official statistics indicate that in France in 1951, infant mortality expressed in deaths per 1,000births was 19.1 in the liberal professions, 23.9 among employers, 28.2 among commercial employees, 34.5 among tradespeople, 36.4 among artisans (craft workers), 42.5among skilled workers, 44.9 among peasants and agricultural workers, 51.9 among semi-skilled workers, 61.7 among unskilled and manual workers. The proportional differences had hardly changed ten years later, although the infant mortality rate had fallen in each category.

[…]

The USA accounts for nearly half of the industrial production and consumes more than half of a great number of primary industrial materials in the capitalist world. Five hundred and fifty million Indians have less steel and electrical energy at their disposal than nine million Belgians. The real per capita income in the poorest countries of the world is only eight percent of the per capita income in the richest countries. Sixty-seven percent of the world’s population receives only 15 percent of the world’s revenue. In India in 1970, 20 times as many women per 100,000 births died in childbirth as in Britain. (pp. 10-11 1979 Ink Links ed.)

It is perhaps useful to reflect a bit on how Rand and her followers practiced Randian teachings in everyday life. As in many “great” movements and religions, the practice was a significant divergence from the theory. Michael Shermer’s book Why Do People Believe Weird Things? illustrates how the Objectivist inner circle degenerated into a personality cult that celebrated the supremacy of one individual and the subordination of the group to Rand as the “Supreme Leader.” Rand’s inner circle referred to itself as “The Collective,” which was either ironic or hypocritical depending largely on one’s perspective and sense of humor.

Rand’s works are riddled with half-truths and historical inaccuracies which she uses to prop up Objectivist mythology. Rand purposefully neglects and ignores the victimization and exploitation wrought by American capitalism, blaming its most acute failures on government regulation and portraying businessmen as innocent “victims” in the essay “Notes on the History of American Free Enterprise” from Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. She acts as an apologist for corruption and greed at all levels, including her analysis of the American railroad system in the early 20th century. Rand’s lapdogs Alan Greenspan, Nathaniel Branden, and Robert Hessen get into the act as well in the aforementioned volume.

Of course, Rand’s perverted world view extends beyond the simple espousal of greed and capitalism but these factors remain at the core of her analyses of any and all social phenomena, including that of racism. For an overview of the Randian take on racism, see her essay “Racism” from the volume The Virtue of Selfishness. One could easily fill an entire volume with arguments refuting and disproving her assertions in this particular work. Rand’s views on women are unbelievably short-sighted and filled with self-loathing. In Rand’s essay “About a Woman President” from the book The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution, Rand wrote that women are “not psychologically suited” to be leaders despite her own ascendancy to an unchallengeable leadership of her own personality cult:

To act as the superior, the leader, virtually the ruler of all the man she deals with, would be an excruciating psychological torture. It would require a total depersonalization, an utter selflessness, and an incommunicable loneliness; she would have to suppress (or repress) every personal aspect of her own character and attitude; she could not be herself, i.e., a woman; … she would become the most unfeminine, sexless, metaphysically inappropriate, and rationally revolting figure of all: a matriarch.

One of the most disturbing components of Objectivism is the Randian analysis of love both as a phenomenon and as a social relationship. Mike Wallace touches on this from his 1959 interview segment:

Wallace: And cannot man have self-esteem if he loves his fellow man? What’s wrong with loving your fellow man?… Why, then, is this kind of love, in your mind, immoral?

Rand: It is immoral if it is a law placed above oneself. It is more than immoral, it is impossible because when you are asked to love everybody indiscriminately, that is to love people without any standards, to love them regardless of the fact of whether they have any value or virtue, you are asked to love nobody.

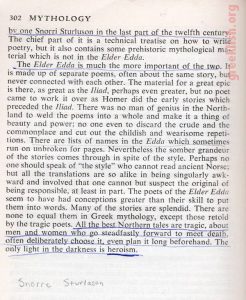

Rand continues by explaining her perception of love as a matter of “self-interest.” The cold, sterile world of Anthem that Equality-7-2521 rebels against in Rand’s work Anthem is seemingly presented for approval by Rand herself in the form of “Objectivist love.” (For an even glibber Objectivist description of the concept of love see pages 35-35 of The Objectivist Reader.) The works of people like Che Guevara, who wrote of the “love of living humanity”, and Alexandra Kollantai, who wrote of love as a cooperative, common, living relationship, stand in direct opposition to the dystopic vision of Randian love. Which kind of love does the world more readily embrace? Love as a form of selfishness or love as a common relationship between equals? Political and philosophical labels aside, I think most of us would prefer the latter.

Rand, for all her rantings on the inherent evil of all other social and economic systems and institutions, sought to build one of the most heartless and draconian systems imaginable through her own propagandistic ravings and her own homegrown cult of personality. It is tragic enough that some of her ideas have indeed found their way into the mainstream schools of political and economic thought in America (thanks to the likes of Greenspan, Friedman, et al.) but we should probably breathe a collective sigh of relief that Objectivism has never gained full credibility and widespread support as an attractive and viable philosophical movement.

The next and final installment of this series will examine the influences on Randian Objectivism on the lyrics of Rush.